Sad Tiger Finally Translated, Joan Didion's Notes, and Some Economics

The second installment of my short story The Amazon and a Brazilian carnaval playlist.

In this week’s newsletter: Neige Sinno’s Sad Tiger English translation is finally out, the New Yorker released a series of Joan Didion’s notes, and a conversation between Ezra Klein and the economic Paul Krugman.

You can read the first part of my short story here: The Amazon I.

The Amazon II: A Short Story

by Renata Mosci Sanfourche

After lunch, which grouped the couples around a whole pirarucu seared in coconut milk and manioc flour, my mother sat courtside watching the wives play tennis. In court the women played doubles, they lacked talent but not costume, they filled the court like a fresh spread in their white pleated skirts, strapless rompers, and red lipstick, giggling like they played this game together many times before. She felt alone, but she was used to not feeling a part; it was often the case in these dynamics that she struggled to find her place. She didn’t like to blabber and when she didn’t have a facialist to recommend, or a hotel in Rome that was close to this café or that boutique, the only other country she visited was Argentina, she tended to close herself off further away, leaving for others a locked, awkward grin on her lips.

So, when the time came for the women to climb into the helicopter to tour the scenic rivers of the Amazon, my mother decided she’d abstain, and the women supported her. “It’s true dear, it’s the best you can do for your baby, you should rest.”

She walked back to her room, past her husband who sat on the terrace with the men, past a table with fresh fruits and juices, past the chestnut tree Princess Diana planted in the garden just a few months prior, and into shelter.

She was too heavy to find comfort in bed and took refuge on the sofa. She left the windows open and welcomed the rain; a light sun shower drizzled on her hairy arms. The wind brought in the smell of wet dirt. She wondered about her son. From inside her purse she pulled a picture of him. His complaisant demeanor, his complicit eyes settled any urge to hear his voice. She dropped the effort and relief took over her countenance.

She thought only of the hours to come, she dreaded the minutes the moon would weigh above her window and she’d have to go to the cocktail reception. She wanted to disappear into the trails that led into the forest, but the laws that reigned over her decisions obliged her to comply. My father was surprised to find her asleep when he came into the room late that afternoon. He expected her to be with the other wives, pursuing the sightings of jaguars and toucans in the forest. He smelled of whiskey and cigars and she despised him, despised herself for tolerating him, for being bound by him. She got up and started an orderly routine around the room which she performed with hastened gestures. She folded her clothes, washed her lace bra and underwear in the sink, fluffed the pillows on the sofa, re-arranged her toiletries, and sorted through her small bags. She showered, dried her hair, put on a minimal amount of mascara, and slipped into a simple black dress to which she added only a pearl necklace. He followed her every move; chased after her like a headless mantis.

Anything he said was remediable that evening for she was at her most vulnerable and dependent when in society, where his charismatic demeanor was her vital companion. When they walked past the women she held his hand tighter, squeezing it a few times before looking up at him smitten, a gesture that implied forgiveness, but he refused to grant her a response and as quickly as she made a move at him, he let go of her hand to latch onto a glass of champagne, and then another one for her. He was not one to withhold cordiality in public, but he knew just the place before intimacy made an appearance. In the bedroom she had wound him with the fervor he needed to spin the room around, even if she wasn’t going to dance along. A few steps in and he already felt full to the brim with the gaze of the ladies, who pivoted their shoulders left and then right to see if he was watching; shame could not abash them.

Waiters in white smokings paced across candlelit halls and salons with silver trays of foie gras and smoked salmon canapés. The guests tiptoed around the salon, treading lightly past the dinner table with gold slingbacks and shiny tuxedo shoes, looking at the seating arrangements from the corner of their eyes and then gathering to discuss them by the fountain. Imported perfumes impregnated the curtains. Plumes and crystals sparkled on crevices of Louis XV sofas. Gold buttons, silver buckles, stone bracelets, and watches affronted the night, and the evening grew brighter and brighter as the company’s swanky guests flocked to the reception.

My mother smiled as she moved toward the piano, her steps delicate and quiet, one hand on the crystal flute, the other playing with the pearls around her neck. She had no trouble recalling the hot February afternoon when my father pulled over in a light blue Chevrolet Chevette. It’s not that the song the pianist played reminded her of the song my father played in the car that summer day, but so rare are the moments in her life when she listened to music, that any song could capture her attention and transport her to another time. It was the roar of an entire nation she heard from his car’s window; Brazil vibrated to the noise of trumpets and tubas, to the showers of confetti that blew through its large avenues where everyone jumped Carnival in wigs, leis, and glitter. My mother and her sisters were waiting for the bus when he pulled up and offered them a ride to the fair. Her sisters were quick to push her onto the front seat, and for the days to come this stranger would lure her into his own.

Soon this impression would fade, the music and murmur of the room would return. She watched him now, surrounded by the grandchildren of bankers, politicians, and important imperial families; businessmen with last names of whom she read only in the papers, in headlines that praised the expansion of this port or the construction of that road.

Certainly she was now ready for a walk; her legs had sunk into the ground and she felt a part with the wallpaper, it did her no good knowing she was just a thread in this room. She got a hold of herself and roamed around the salon. The choreographed mannerisms in people’s hands, the meandering of the staff, the out of season peonies, she felt far from home. In a distant place, south of the Amazon, in the sparse mountain ranges that protected her hometown, she pictured her sisters huddled around a game of cards, worried only about the livestock outside. As for the success of the evening, the significance it had for my father, she thought little about it, on her mind was only how trivial it had all been thus far, and the little effort everyone had put into making her feel wanted. She had no desire to partake in it. She was always so certain of her perspectives, of her interpretation of their perspectives, not once did it occur to her that she might be wrong. She saw only what she wanted to believe in, a people living between hair salons and dinner functions, relying on the poor to prepare their affairs and regarding with kindness only those few doctors and lawyers they’d come to rely on.

A cold front brought a small crowd back into the main hall. The prospect of fresh air made her even more contemplative. “Can you please open the door?” Her tone, crass and impolite, was just as shameless as the men who ventured in wearing a cashmere scarf, mingling with senior officials.

She wrinkled her nose. At night, when the air was thin, the wind brought to the summit a reminder of the sedulous miners: a metal and carbon stench. From the terrace she saw for the first time the iron ores where very bright lights exposed the depths of the holes Vale was digging into the Amazon; their glow outshined the moon. It was as close to hell as she could imagine.

She was the only one outside, no one else had come to look at the sky, and she thought about the magnetism that beckoned her into my father’s arms, how it was nothing but a plot against her reality, and she kept circling around these inferences until she heard Nina’s voice.

“My grandmother never wanted a fountain here.”

“Well, I wouldn’t say she was very strong willed,” replied my mother turning her head slightly toward Nina.

They smiled at each other as they stepped back into the main hall.

“Now where are we supposed to sit,” said Nina.

“Ana!” said my father.

“We’ll know soon enough,” she insisted.

My mother withdrew from her lone soldier stance and moved back into conformist wife. She wrapped her hand around his arm. He took them around the table while they poked into the empty seats to see if one of them read their name. In the distance she tried to find someone to guide them, but help was out of her reach. It was a relief when a man signaled from across the table pointing them to their seats. There they found their names calligraphed on porcelain plates, where, in the middle of the Amazon, they would taste the six-course French dinner; gougère with oysters, salmon mousse, sole meunière or coq au vin, salad, beaufort, and a demitasse with a slice of tarte tatin.

You can read the end of this short story here: The Amazon III.

A Visual Library

Currently at Rue de Chabrol

Five articles I read this week:

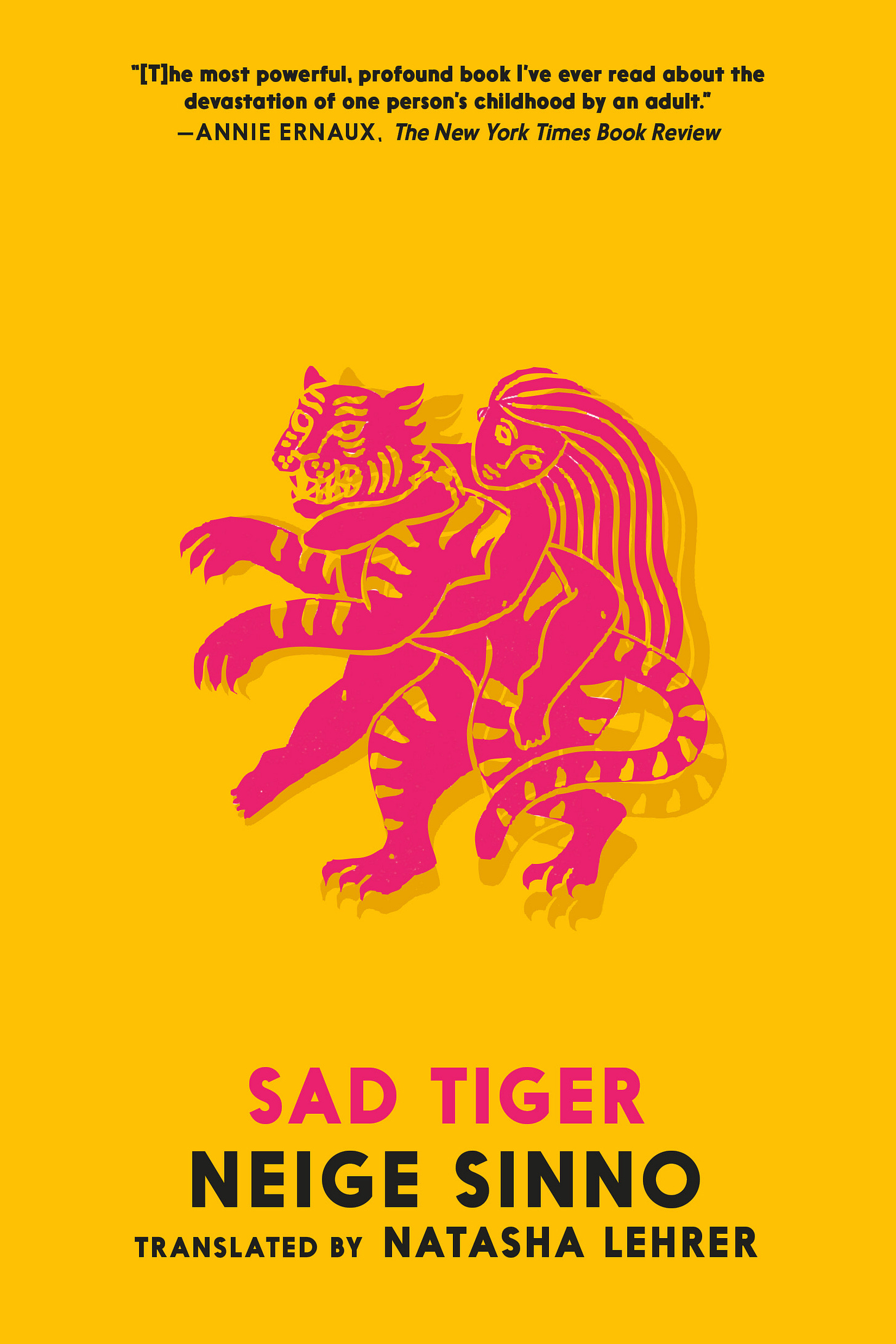

My therapist recommended I read Neige Sinno’s memoir Sad Tiger earlier this year. I read it in French because it wasn’t translated to English. I left the book feeling like it was an urgent reflection on abuse; the perspectives around abuse and what it means to try to understand your abuser. It’s now out in English.

Ezra Klein invited the economist Paul Krugman to talk about tarrifs.

An In Our Times episode about Pollination, accompanied by an excellent reading list (screenshot below). If I could add one more title to this list it would be The Intelligence of Flowers by Maurice Maeterlinck.

David Cole reviewed two books about the relationship between politicians and universities in what feels like a timely moment, all for the New York Review of Books.

The New Yorker posted a series of notes Joan Didion wrote to her husband John Dunne before he and their daughter passed away. The notes are a sort of recap from her sessions with her therapist. They will be published as a book called Notes to John later this month. And here’s a beautiful picture to remember Didion by this morning.

What my husband is listening to:

What my daughter is into: a friend at school making milk with yoghurt and water, looking at herself in the mirror, short sleeve dresses because it’s getting warmer in Paris, and my ultimate favorite, using my eyebrow gel to brush her eyebrows down.

A movie I’m thinking about:

La Notte by Michelangelo Antonioni

A Poem

A Glimpse

by Walt Whitman

A glimpse through an interstice caught,

Of a crowd of workmen and drivers in a bar-room around the stove late of a winter night, and I unremark’d seated in a corner,

Of a youth who loves me and whom I love, silently approaching and seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand,

A long while amid the noises of coming and going, of drinking and oath and smutty jest,

There we two, content, happy in being together, speaking little, perhaps not a word.