Mexican Folk Art, Ross Posnock at Yale, A Brief Introduction

An introduction to Rue de Chabrol, a Mexican folk art book, a lecture at Yale by Ross Posnock, and more.

Dear Friends,

For the last eight years my days have been a complete mess. I jump between writer, mother, editor, handweaver, reader, classics enthusiast, wife, listener, good friend, bad friend, researcher, essayist, therapy patient, alcohol enthusiast, shopper, homeowner, journalist, I mean the list goes on. Yet, no matter how many characters I fluctuate between I am still a stranger to myself.

Inside it’s a tug-of-war between a sense of myself and a reflected sense of myself. I find in no place a concrete and foundational idea of who I am and could abide by. In this paradigm I forget myself, I am daunted by the prospect of constructing myself, and I am paralyzed by becoming. I am incubating inside my own experiences.

The coffeeshop owner downstairs confides in me his business problems and I leave with a latte and his struggles. My upstairs neighbor offers an opinion on my parenting skills and it torments me for days. A friend wants advice and their problem becomes my occupation. I’m as malleable as marzipan.

In order to materialize what I create I have to prepare, to be ready to find a new confection. This moment, of personal knowledge, has finally arrived. I am now in safety, I have survived, I have built and destroyed, and now it’s time for me to become, to understand. My personal knowledge is in my feelings, my instincts, my opinions, and I’m putting all of those here.

At home on Rue de Chabrol I am sifting through my dirt to give you all the things I find are gold, all the words that are changing me, and everything else I spend time on instead of writing my book.

Welcome!

In this week’s newsletter:

1995, The Broken Vase: A Chronicle

by Renata Mosci Sanfourche

The vase broke on the fifth try. It was mottled amber with an iridescent embossing of a castle by a lake. It was signed near the foot in cameo ‘Evelina’. She knew she would have to hurl it many times against the curb before it shattered into pieces over the gutter. At first, she mounted her arm high above her head, mustered all her force and thrust the vase toward the pavement, but the vase rolled down the street intact. With each throw she lashed out more, aimed more strategically, but it was clear that neither strength nor design would break this vase. When the fifth try came around she lifted the vase in front of her like a crane, hoisting the handle with her fingers. When her arm was fully stretched she let go of her hold and the vase broke at once into pieces.

We were a standing army on the backstreets of Rio de Janeiro, just meters away from our house. She collected the pieces, trees and lake shards in one hand, the castle and sky shards in another, and with her bare hands placed them on the bottom of a plastic bag. There was no blood, she left no evidence of her doing, and on the way back to the house she buried the bag under a small slab of concrete inside an orange construction dump.

“Didn’t I tell you,” she boasted. “It wouldn’t break on the first throw.”

Existence as she presented it to us was solely spiritual. The magnitude of her imagination led us down ethereal paths where there was no grass on the ground, no shade, no sun. Where all that moved us came with another time. We were surprised by the vase’s resilience that morning, any child witnessing such foresight would have registered what passed as an unusual act. Yes, it was quaint, but so were a lot of things about my mother. She’d wake up from a nap and throw away the iris bouquets she had just ordered the day before. She’d tell us the pyjamas we wore to breakfast needed to be thrown out. Sometimes she’d come into my room and take a brown mallet to all my music: Britney Spears, Michael Jackson, Madonna all sat crackled on the carpet while I stared at her walking off with relief. To me it was ordinary.

My brother took after her. At first he was aggressive in school, but soon he directed his anger toward me. If I insisted on watching a cartoon next to him after school, he pushed me to the floor and kicked me until I couldn’t feel my limbs anymore. In the evening I’d notice my legs covered in bruises before I showered. My mother never mentioned it. One never knew who drew the blow. When she was irritated, or if she’d ever catch us fighting, it didn’t matter who was in the right or the wrong, she would bring a whip from the kitchen and with the strength she used to throw that vase, she would draw thin lines of blood and peeling skin around our stomachs, arms, and legs.

“Withhold not correction from the child: for it thou beatest him with the rod, he shall not die. Thow shalt beat him with the rod, and shalt deliver his soul from hell.” She repeated this Proverbs so many times.

It was customary to see her planting the perennials just under the trees with the green thorny rods. When they were ready, she’d clip the leaves off the sticks and keep them in the kitchen. They lay green, brown, and strong in the same fruit basket she kept mangos and papayas and cashew fruits. Sometimes my brother would break the whip so when she would grab it it’d be useless. In these instances she’d turn desperate and be all together done with the impulse. At first it worked well, but after a few days she took to the belt, and then the belt became a household staple. I can still hear those belt whippings. I hear the whooping sound the leather makes as it pushes through the air until it hits surface. There were times when she’d be so overwhelmed she’d lash the belt forward over and over again until it hit us both. It was a savage scene: two frantic children running around the house trying to find or make a bunker before she striked. She wouldn’t even aim. Once, after she hit me on my groin, I stopped seeking refuge around the house and would instead run to my room and put on as many layers as I could find. I looked at her quietly that day though, into her inflamed eyes, and for the first time felt a pain much greater than those lashings ever felt.

Some days, after locking us in our bedrooms for hours after a surge, she would come running to us, arms filled with tenderness. On those nights we ate dinner together, laid next to her in bed, and each got to pick a worship song in her black book of hymns. The gospel was nothing other than our reward, and the only path through which she interacted with us affectionately.

Because you make so little impression, you see. You get born and you try this and you dont know why only you keep on trying it and you are born at the same time with a lot of other people, all mixed up with them, like trying to, having to, move your arms and legs with strings only the same strings are hitched to all the other arms and legs…like five or six people all trying to make a rug on the same loom only each one wants to weave his own patterns into the rug; and it cant matter, you know that, or the ones that set up the loom would have arranged things a little better.

— Absalom, Absalom!

It is for you to decide rather this path becomes something beyond experience, it’s your choice to make it exist. What lies ahead isn’t a consolidation of the past or orderliness of the future, it is the chaos of the present. It’s confused, disorganized, the language isn’t sharp, the product isn’t final, and it attempts only to illuminate the very process of its formation. I am unsure a sense of myself will emerge from this incubation, perhaps it will, but having failed to complete and having struggled to continue, I understand only that the process is most revealing, and I have found no other medium, not in theatre or film, not in literature or essays, to share my work as naturally as this one.

Mexican Folk Art

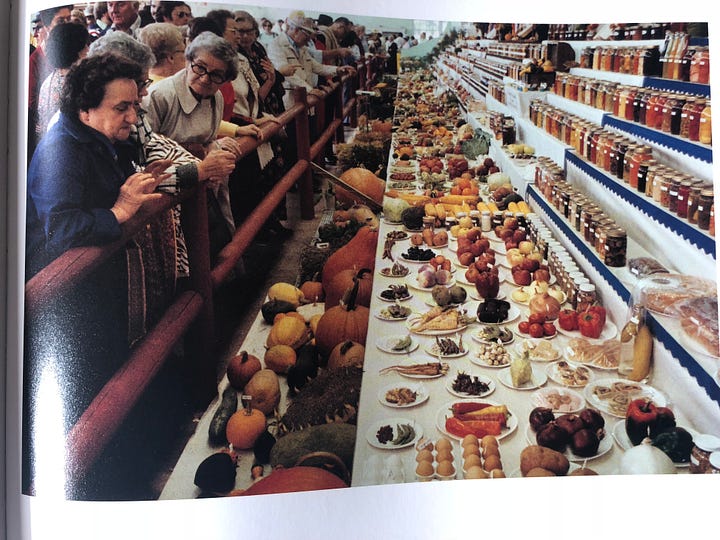

I keep thinking about this vase, about what she destroyed that day. At some point the story couldn’t progress until I was able to see it whole, to bring this object back to life. It was stronger than me. I remember turning to my bookshelf and looking at the titles to see if anything jumped out at me. Without giving it much thought I reached for a Mexican folk art book I offered my husband a few years ago on his birthday.

The technique Esther Medina Hernandez uses was passed down to her through generations of artisans in her community in Coronillas. Her parents, and their parents, were all potters. Esther took what they had done for years, what they had taught her, and she created something new; a style with an inimitable texture that’s particular to her.

Hilario Alejos Madrigal’s mother taught him to work with clay when he was only fifteen. She was a famous Michoacán artisan known for her Carapan pineapples. He worked in the same style as her but developed a unique appliqué technique that turned him into one of Mexico’s most celebrated ceramicists.

—

There are countless stories in this book. Reading them, looking at the artefacts these artisans make, instilled in me a sense of profound sadness. I was jealous to see how generations of children could preserve such fragility, a vulnerable practice, growing it, transforming it, mastering its beauty, building something together with their parents.

The Evangelical, Fundamentalist Mother

I’ve only recently understood what christian fundamentalism can create. It happened in a session with my therapist who I’ve been seeing for seven years now. During this entire period together I have rarely discussed my upbringing in religious terms. It was such common practice at home that I didn’t think about bringing it up when we were discussing certain childhood events. Yes, my mother was very religious, but I never went too far into what it meant to our becoming that she was religious. Today, I have travelled so far from this reality that I don’t think it would cross anyones mind that by religious I meant fundamentalist.

It was only when I explained that my mother’s relationship to God was premised on her fear of the devil, that we started understanding that I grew up in a sect. It’s very difficult for me to speak about this concept in English because evangelical christianity in America is very rarely interpreted by its believers in the same context that it is in Brazil. In Brazil, it emerged as a reaction to the development of other belief systems like afro-brazilian or native-brazilian religions. Over time, the church instilled in me the primary belief that all other religions, including catholicism, either belonged to the devil or were corrupted by the devil. Under the foundational ideology that Lucifer fell from the sky to dominate earth, evangelical protestants including my mother, were here to subvert and transform the work of the devil. And it was under this reality that she operated.

When my therapist used the word “fundamentalism” to describe this practice I was shaken. I had come to associate the word with other religions, but not with Protestant Christianity. In fact, when I looked up the word in the Merriam Webster dictionary I was surprised to find that the definition refers particularly to Protestant Christianity: “a movement in 20th century Protestantism emphasizing the literally interpreted Bible as fundamental to Christian life and teaching.” It couldn’t be more clear.

I have constant flashbacks to my mother repeating passages of the Bible. It was daily practice in our house, one that submerged any other governing system in my universe including science, history, philosophy, economics, language. The notion that one can justify ascribing pain under these guiding principles is mortal, unpardonable.

Renunciation by Ross Posnock

A tribute to Harold Bloom whose work has taught me everything.

I’m hooked on the Yale University and YaleCourses YouTube channels and have been for quite some years now. I read Dante’s Inferno while watching Dante in Translation on YouTube with the historian Giuseppe Mazzotta, and I can’t recommend it enough.

What comes to mind here is a lecture by Ross Posnock, “On the Pleasures of Self-Misunderstanding: 'How One Becomes What One Is' in Nietzsche and Emerson.” I highly recommend watching the entire lecture, and if you want more he also wrote a book “Renunciation Acts of Abandonment by Writers, Philosophers, and Artists”.

A Visual Library

Currently at Rue de Chabrol

Four albums and one single my husband is listening to:

What my daughter is reading right now: Les Aventures de Pépère le Chat by Ronan Badel and La Fabuleuse Histoire de la Poire Géante by Jakob Martin Strid.

A film I’m thinking about:

Under the Sun of Satan by Maurice Pialat (1987)

A Poem

Forgetfulness

by Hart Crane

Forgetfulness is like a song

That, freed from beat and measure, wanders.

Forgetfulness is like a bird whose wings are reconciled,

Outspread and motionless, —

A bird that coasts the wind unwearyingly.

Forgetfulness is rain at night,

Or an old house in a forest, — or a child.

Forgetfulness is white, — white as a blasted tree,

And it may stun the sybil into prophecy,

Or bury the Gods.

I can remember much forgetfulness.

FYI: the holding image for this post features work by Dutch artist Bouke de Vries.