Richard Prince's Book Collection, an Interview with Maggie Nelson, and a Chronicle

Five articles I read this week, a chronicle I wrote, and Walter Benjamin's newly translated paper.

In this week’s newsletter: a chronicle, Richard Prince’s book collection, five articles I read this week including an interview with Maggie Nelson, a newly translated paper by Walter Benjamin, and more.

The Rio Negro: A Chronicle

by Renata Mosci Sanfourche

“How can we live without our lives? How will we know it’s us without our past?”

- John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

I veered the canoe out of the stream into the blackwater river. Behind me, the water rippled outward, revealing each curve of the flooded forest painted softly upon its surface. With each push of the paddle my voyage expanded ahead and I emerged from the canopied tributary into the boiling sun, my temples dripped with sweat and I waited on the bank for the heat to subside. I watched the remains of the forest rot into amber freshwater. The Rio Negro, a river unfit to decompose its past, each night I saw it die only to reemerge in the morning.

Earlier that day I was swinging on the hammock, my legs dangling over its frayed edge while I counted leaves on the glass ceiling of the veranda. For years my family spent summers in this house, where I was content to roam outside, to put my hands on the trees, let the ants crawl up my arms, and to crush them on my skin to keep the mosquitos away. I read the books we kept next to indigenous artifacts. Bows, arrows, headdresses, coconut bowls were carefully placed next to monographs of faraway cities like Prague, Sydney, and Bogota, books my father collected as souvenirs at airport gift shops. At the time everyone visited the Amazon to find something. Scientists sought miracles, artists sought awakening, environmentalists searched for reasons, miners for ore, executives for power, and we just wanted to be near my father. I read those books to forget the singular landscape that had become the jungle over the years, where the fruits tasted stale, the radio and birds sounded redundant, the walks in the forest became tedious.

After sundown I paddled again. This time to the smell of a rotting river, a sour stench that grew stronger with the night. It didn’t take long before I crossed over and north to the western side. Once I reached the floodplains I hid my paddle in the canoe and lugged everything up to land. I took the path I knew so well at daytime, when I left home to buy tapioca or post letters to our family. The lights and the chatter of the local people paved the way. This was the settlement that connected us, where we could leap from home to the unknown. This is the frontier, where we’ll be forced to go far into our thoughts, into our memories, where what we describe, what we see, and where we are is not what we write until we’re home.

It was infinite: the trees, the trampled grass, the sound of people, it knew no bounds and it was vast. I was as much a foreigner in this clearing as I was on the hammock in the house. I walked and walked, past the locals on white plastic chairs drinking cold beer in short glass cups, past the woman from the newsstand on a bench holding a bag waiting for her grandchildren, past the men playing canasta for a couple of bucks, past young couples holding hands, televisions tuned to soap operas, young children eating popcorn, and grown children playing ball. I kept walking until I reached another glade. I couldn’t make out what was ahead, the village backlit the way and my steps turned darker and darker. I could not rush the order of the world. Out there in the forest, surrounded by the wilderness, one step from the jaguars and another from the poisonous frogs, I was finding something, a thought of my own.

I turned around and paddled back to my house. The horizon was black and I saw only as far as myself. I was sweaty, I smelled of guava, my hair was messy, and it was hard to paddle against the current. Water moved in and out of the canoe, my boots got wetter. My palms were covered in blisters and my stomach growled. I breathed a new air up my nostrils, my own mannerisms started to feel alien to me, and there was a shift happening. I would come to experience this shift once more in my life, and when I did I would know what to expect, but here the air was entirely new, it was strange, and I didn’t know I wouldn’t find that self again, the one that stayed on the other side of the river like the old skin of a shedded snake.

I tied the canoe around a wooden stub on the dock. I wondered if the fruits would taste the same, if the cracks on the walls, the floor, the ceiling would still be there. I looked for that careless feeling when we arrive at home, when we can kick our shoes off, open the refrigerator and sit, but it wasn’t there. The house was dim, neat, and the glass ceiling had been wiped clean. The hammock had been folded down.

The house was cold. I saw it in ruins, shattered and demolished into the ground, but I couldn’t move forward without it. There was no room, no floor, no shelter, all that existed was a hallow space from which things moved without order. I had to do what was most important, look forward and remember.

I forgot a great part of this house. I forgot who they were and what I found. There I was just moments ago on the canoe, between now and then, where all was clear but dead, as dead as the leaves on the riverbank.

How little one knows what only nature can explain, how a river so mysterious can resound with such clarity. It is far too obvious to look up and see, far too light, but to look down, into the depth, into the decay of the forest, where the past and the present are crippled in time, that’s where we find truth, and in honesty lies beauty.

A Visual Library

Currently at Rue de Chabrol

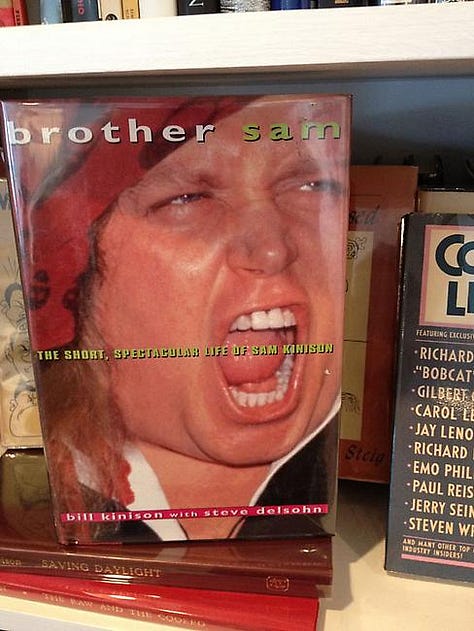

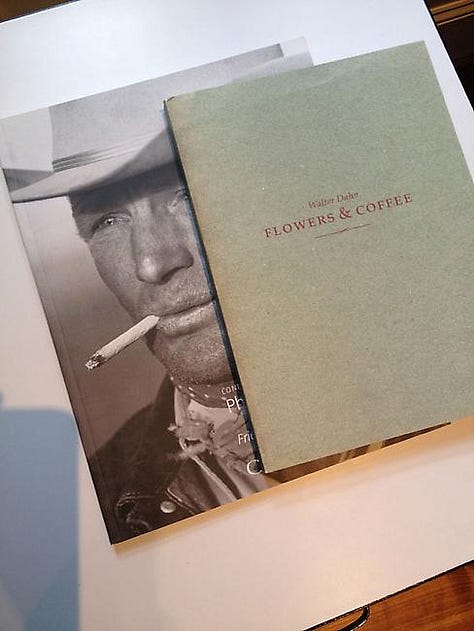

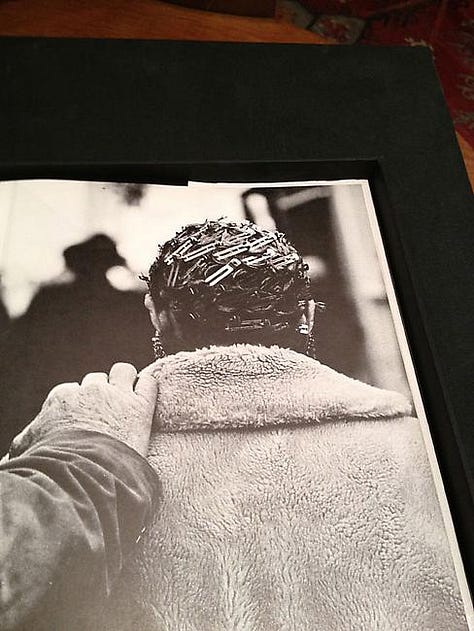

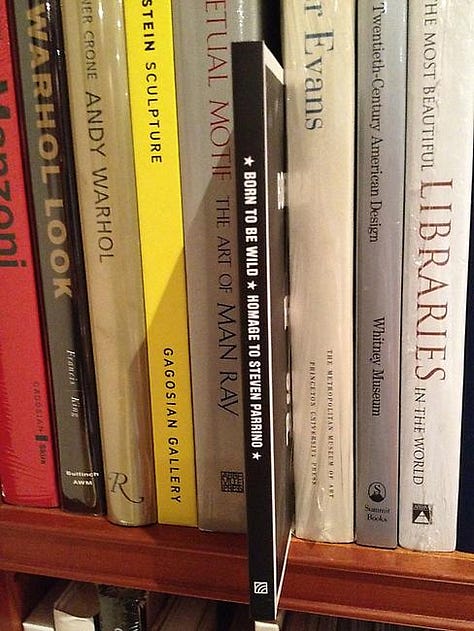

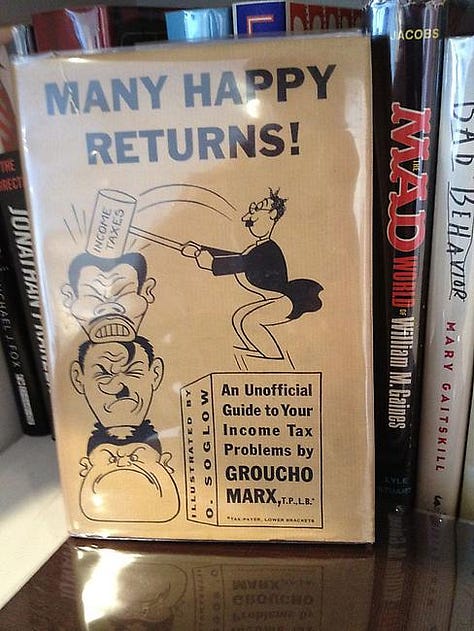

Looking at Richard Prince’s book collection: when I lived in New York I always ran into Richard Prince at the antique book fair, and I was always very curious to know what he was buying. I don’t think he’s documenting his entire collection on his website, but it’s interesting to look at some of the works he’s got in there.

What my daughter is reading right now: all the “Matous Filous” books by the Japanese author Noriko Kudoh. Translated by Alice Hureau into French.

What I’m reading in the morning: Alice Munro’s short stories in “Too Much Happiness”. I wish I had read them before she died, before her daughter accused her of doing nothing to stop her abusive stepfather. Knowing what we know now, it’s difficult to read her depiction of abuse, her questions about justice and morality. Were these stories her way of expressing her feelings about the issue?

Five articles I read this week:

Brian Owens wrote about the chatbots claiming to be Jesus Christ and offering people a chance to speak with God online. (Nature)

“None of the chatbots he studied were developed or endorsed by any church, and it is not clear what religious texts they were trained on. Four of the five were created and managed by private companies — with names such as Catloaf Software, a mobile-development company in Los Angeles, California — whereas the fifth is run by a Christian group in South Korea with no official connection to any church. All are free but supported by advertisements, with one offering an ad-free premium subscription.” — Brian Owens

Edmund de Waal’s essay How Mrs. Dalloway Began about Virginia Woolf’s sentences and the creative process that led her to write Mrs. Dalloway. De Wall originally delivered this essay as a talk at the Charleston Festival in Sussex. (The Yale Review)

Maggie Nelson’s interview in the new issue of the Paris Review. (The Paris Review)

Last fall, Michael Krimper translated Walter Benjamin’s 1939 paper “Notes on Baudelaire’s Parisian Tableaux” originally written in French. It was published in October, Rosalind Krauss’s academic journal that specializes in criticism and theory and is published by the MIT Press. (October)

“What is the writer’s social role in the twenty-first century, when we seem to be caught in the same antagonism between democracy and fascism, albeit one aggravated by the ever-expanding and totalizing reach of capitalism? Perhaps the afterlife of the “Notes” can shed new light on the aesthetic and political stakes of Benjamin’s reading of Baudelaire at the intersection of numerous unfinished projects and struggles in 1939, as well as his many still reverberating encounters and affinities with insurgent constellations of literary, social, and critical theory in twentieth-century France and beyond up to the contemporary period.” — Michael Krimper

The New York Times reporter Scott Reyburn decided to follow the assignment of a Harvard professor and spend three hours in front of an artwork. He chose ‘Las Meninas’ by Velázquez. In this article he shares the notes he took during the immersive experience. (The New York Times)

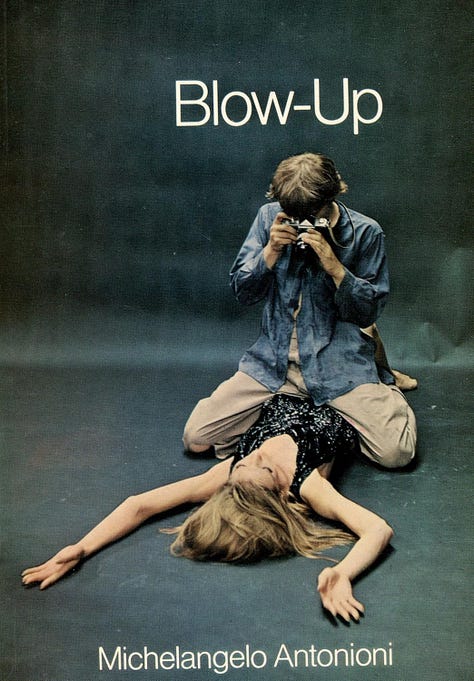

Movies I’m thinking about:

The Castaways of Turtle Island by Jacques Rozier

A Poem

Banish Air from Air

by Emily Dickinson

Banish Air from Air -

Divide Light if you dare -

They’ll meet

While Cubes in a Drop

Or Pellets of Shape

Fit -

Films cannot annul

Odors return whole

Force Flame

And with a Blonde push

Over your impotence

Flits Steam.