In Conversation with Luc Tuymans, Reaching New Heights

The Belgian artist Luc Tuymans talks to me about his upcoming show "The Fruit Basket" and what it means to be an artist in today's reality.

IN CONVERSATION WITH

Luc Tuymans

by Renata Mosci Sanfourche

Something about Luc Tuymans’ upcoming show ‘The Fruit Basket’ reads different from his previous exhibitions. The paintings are larger, more complex, and brighter than the works we’re used to seeing him present. Last week, when we sat down to speak about his practice, and the rigor that makes Tuymans the most important painter of our times—he’s credited with reviving painting in the 1980s and influencing a generation of artists—I left with an urgent reminder: it’s impossible, and irrelevant, to try and escape today’s reality.

In just a few days, at David Zwirner’s Los Angeles gallery, visitors will discover a series of new paintings by the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans.

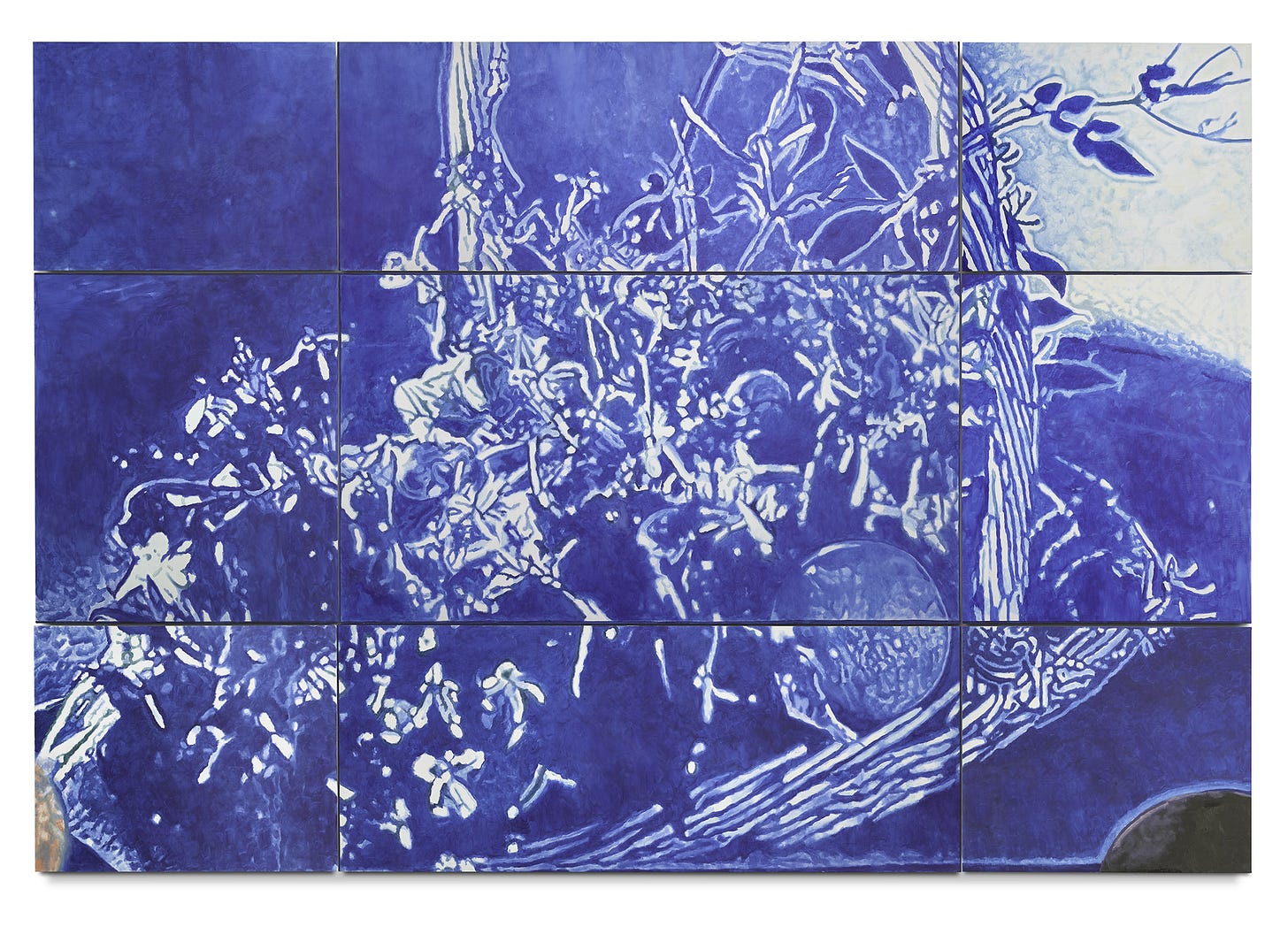

They will encounter The Fruit Basket, the largest painting on view that lends its name to the exhibition. No matter where one stands, it will be impossible to avoid the five-by-sixteen-meter blue image fragmented into a nine-canvas grid and hanging as one piece. As one makes their way closer to the painting, they’ll notice it was once an iPhone picture of a fruit basket—we can see the artist’s thumbs on the bottom edges of the work. When one is but steps away from the painting, their proximity will start to impair their perception and the fruit basket will disintegrate into purposeful brush strokes.

Just like fruits rot, the painting also dissolves, reminding spectators in the United States of their proximity to the degeneration of America. Distance is integral to all of Tuymans’ work, as are the complex moral questions he observes. Over the years, it’s the scale of his paintings that have changed. Today, what reads different in this series is his achievement with light, with color and contrast, and Tuymans explains why: this is the first time he’s been able to paint digital light.

What follows below is a conversation that attempts to trace the evolution of his work. The more you understand about Tuymans’ capacity to capture reality—not romance—and his responsibility and self-awareness with his medium, the more you can appreciate the distance he sets between his work and his spectators, and thus the disintegration of his images, the fogginess in his paintings as the reality of the human condition. These are forces he casts to help us rethink our conception of the past, of humanity and their moral concerns, and the value of painting within this landscape.

Your work can be extremely difficult to process at different levels. For one it’s quite violent, sometimes even painful to sit with, and these qualities present themselves as early as when you started. Where does this feeling come from?

I don’t know, maybe it has to do with the trajectory of life itself and my vision of the world which is not really that optimistic, it’s more of a pessimistic feel for the world because you have to be prepared for things that can happen.

I’m also convinced that in a way things that are making people happy will last 30 seconds. The consequences of violence in any which way or form are gigantic. This also goes to the visual level in the sense that it creates a different form of visuals. That fascinated me and it’s why I also never wanted to make art from art or for art’s sake, but mostly art based upon either an experience or the real so to speak. That’s why I sort of tended towards that notion of a reality.

Were you exposed to violence during your upbringing?

Up until I was 15 I was probably to a certain extent autistic, I was very quiet and all that, and I was bullied at school during that period until I eventually grew and it all turned around. So that probably also enhanced this notion of the idea of cruelty and especially kids, how cruelty has an element of ignorance that plays out, being uninformed, not knowing, not taking the time to know things, and then actually this blunt element of violence which is something that probably enhanced that situation.

I said this many times already—the marriage of my parents was not really happy. There was also the situation that they both were in different camps during the same world war. There was always this situation while we were eating where this came up, there was this tension that was constantly there on different levels.

There’s also my assessment of course that after the second world war, Europe as an empire was dissolved, the colonies were dissolved, and this is sort of a building block for where we are now. Look where we are now. If you do this whole trajectory it explains a lot, and at the same time it doesn’t. That is the conundrum we find ourselves in, and I find this conundrum quite interesting.

In your catalogue raisonné, your paintings are documented starting in 1978 when you were 20 years old. What questions were you asking yourself then?

I was very young. First, painting was quite a problem during that time because it was seen as an antique. I had to revalidate it in a way that would make sense and that’s why I came up with the idea of the authentic falsification.

At first it was quite regressive and I wanted to make work that looked older than it actually was. I wanted to continue painting, because painting is all about the touch, and it’s a medium that grew on me and was appropriate. In the beginning it was very juvenile, it was very existential and tormented which I started to hate and that’s why I stopped painting from 1980 to 1985 when I started working with film, and then I came back to painting informed by film.

Can you talk a little bit about this torment?

The typical sort of romantic idea of the artist who is not doomed but in a sense feels this sort of weight with the world. It’s a selfish proposition and it’s a kind of stupid and naïve one, it doesn’t have enough distance actually. In order to create visuals you need distance.

Through the lens of the camera I achieved that distance and then I could go back. Because I evolved from Super 8 to Super 16 to 35mm, it became expensive, that was one thing. The other thing was that I didn’t have the right script. Then I started to paint again and I found out that this was really an evaluation I’d been making over the last five years. It enabled me to actually paint things that I didn’t have the distance to paint what I wanted to paint then.

There was also the connection between film and painting. I would be a very bad photographer because I would never be in the moment. With film and painting you can approach the image because it’s a different assessment. I mean you can overpaint a painting. You can actually edit in the lens while you’re filming, you can approach the image, so that was quite interesting as a perspective.

Distance with the spectator is also important to you.

Every great artwork is about positioning, and positioning on different levels, and what you mean about how the work is relevant, but also positioning towards the spectator. Even old masters have a real sense about how that will work.

For example, Velázquez used to work with an elongated pencil on a stick in order to see what the distance measurement would be for him, but also the spectator. The distance you measure between the image and the spectator is actually part of the work, and that’s why when you see an image of mine at a distance it will sort of make sense. It’s also important for me to work from a distance. That’s also why I work with a hand mirror that puts the image upside down, to see how it really works. Once you get closer to the image it will sort of disintegrate.

Can you explain this distance and the detachment this creates in your work perhaps through the 1992 series Der Diagnostische Blick?

I was always interested in medicine to a certain extent. I had my opening at the Kunsthalle and at that point I hadn’t painted a lot of portraits. The ones I painted were portraits that I dreamt up and that were halfway self-portraits. Those were the ones from the ‘70s, most of them I destroyed and overpainted, some of them still survive but not many.

So I wanted to paint figures again but not in terms of a psychological perspective. At the opening, I found a psychoanalyst and I asked if they still had these books students use from photographed subjects, with people they would use to make a diagnosis. He said he’d send me these books and out of that I culminated a whole series which is called A Diagnostic View.

It’s interesting because it’s the most naturalistic in a sense, but at the same time this was also the first time I started to apply paint in a horizontal way so that it flattens the surface of the painting and makes it into a barrier where you cannot enter. The paintings turns into a symptom and although it’s very naturalistic it’s missing the real completely. That was the angle.

You’ve said before that Our New Quarters (1986) isn’t your most famous painting but the most important one. Why?

It’s important because it’s about a taboo and because I never lived through the second world war, so there was a moral problem of could you touch up to this specific content. This particular painting came about because I found a book by Alfred Kantor in a bookshop in Antwerp from 1979. Alfred Kantor had survived three concentration camps—Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Schwarzheide.

A couple of works were culminated out of that, this one and Schwarzheide (1986). The first one was based on this postcard. What was interesting was that he didn’t write a diary, he made a whole book with drawings. In the beginning of the book he glued these postcards which were handed out in the very beginning when he was in Theresienstadt—a sort of mass model camp they used in propaganda. They gave the inmates these postcards to send to their relatives. Of course he had written in Czech, because he was a Czech Jew, in Czech this is our new quarters. In New York—because he died in ‘79, he lived in New York—he glued them in the book and underneath he wrote Our New Quarters, which is as if nothing had changed in between which I found interesting.

I used the backdrop of a military green color which gets darker on the edges, and then very fast made the contour of the Kasematte, which was an existing building in which they were all gathered. The interesting point is when he was freed he was repatriated to the same spot where he departed from after surviving the whole thing by the Russians, they were repatriated after this Kasematte in Theresienstadt, and he stole a box with these postcards.

By using a sort of white so slightly mixed with yellow undertone, it sort of lights up and gives the idea of a subtitle nearly, so it becomes like a documentary nearly. In that sense it’s an autonomous painting as is the Gas Chamber that came later and so on.

You understand yourself as a Flemish painter and you’re attentive to the lineage you’re carrying forward in that role. You love Jan Van Eyck, you trust in the work of your Flemish predecessors, and you demonstrate an enormous sense of responsibility. Why is this important to you?

When I was nine years old, I was in front of a Van Eyck painting and I saw this and I thought I can’t forget it, this is it. It was an extreme form of perfection. It was important for the entire Renaissance because it was the first time there was enough distance to open the window to the world.

The brothers Van Eyck did not completely invent oil painting but they perfected it. It was then imported into Italy and enabled Leonardo da Vinci to make his first masterpiece. He also had a very interesting motto, if I can, which means I’m big on humility but behind that I have gigantic ambitions.

What’s more important to understand is that the entirety of Belgium, which is a dreamt up country—and a young one, it’s younger than the United States—was given back to the Dutch after the Napoleonic Wars and nobody knew what to do with it, the Rothschilds bought it, it was a tax paradise and they put a king on it.

Flanders was also a region, never a country, it was always under foreign rule, but it was important because of that. There was no time to be romantic or rational like the French, or romantic like the Germans, there was this opportunism within the idea of survival. So the element of the real is really important.

To give an example, people talk about [James] Ensor and say he’s grotesque. He’s not grotesque, he’s a real precursor of expressionism as a soul within that framework. Then you have Magritte whose most famous painting, La Trahison des Images, where you see a pipe and under which he writes, this is not a pipe, of course not because it’s the image of the pipe.

So it’s much more about the real in this part of the world than something else, and that’s what connects it back to Van Eyck, who by heightening the real was able to contract itself from the mnemonic imagery of Christianity, opening it to the world. That is an important statement.

In a sense you cannot get away from the contemporary, you will evolve if you like or dislike it, it’s going to have an impact.

How do you overcome the influence of Van Eyck?

I’m not influenced by Van Eyck because I could never do that, so I’m not even going to try doing that. You have to accept you’re a dilettante in this iteration, accept your position, and work from there. I don’t also see any purpose in trying to mimic it, because that would be impossible and not really interesting. It’s just that you have to validate it for what it is.

In this process, where do you find your freedom?

When I’m working. Although I prepare everything extremely well—I make a lot of drawings—it takes a lot of time before I start the painting process. When I actually start painting it goes pretty fast. At that point, I don’t want to think anymore on the canvas. Some painters do, but I don’t. There are exceptions, there are painters who have changed, but very few. In that sense I know very well what I’m doing, but nevertheless you don’t know everything; there’s always something that sort of escapes you. By concentrating and letting the intelligence flow into the hands instead of the brain, you get an element which is extremely intentional, which is extremely nervous, which is extremely poignant. The first three hours of painting are hell, but when it starts to fall together that’s when the picture starts and you can do things that with the naked eye you know nobody would see but that are fundamental to the image in itself. That’s specific pleasure, and it’s also the pleasure of painting. If I wouldn’t have this tension and this pleasure of doing it I would just discard the work and then I would not do it anymore.

What happens to you at this precise moment when everything that’s inside your head becomes physical?

I don’t think about it. I’m activated. I’m doing it. It takes so much concentration I don’t want to think, I just want to do what I’m doing. As I said the intelligence goes from the head to the hands which is a different intelligence. And I think that’s very important. It’s not that I set out to make a painting in one day, because in the early days I painted for much longer, but at a certain point it grew organically to set myself this sort of situation to go through.

It also changed when I started no longer living in the studio, when I destroyed a lot of things because I worked a lot on it. During the relationship with my first girlfriend, when I was able to move to her place and use my apartment as a studio, I could make this distance, then disturb it and start to work to make a painting in a day, or paint to a point where I would say okay, maybe little changes the day after, but to come back the next day and look at it, if it worked or not. If not, I would destroy and overpaint it. Now I can afford to throw it away and start again in a new canvas.

Do you ever work from your own memory? Could you paint something that’s not visible?

I did work from my memory. There are some works solely made on memory. In the beginning it was a bit more. There were memories from drawings I made and reconstructed into paintings. It still happens, it all depends, it’s a cluster of different things.

Postmemory is a concept Marianne Hirsch developed at Columbia University. She defines it as: “the relationship the generation after bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before-to the experiences they remember only by means of stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up.”

One of my first works about memory was the painting I made about the brother of my mother who died during the war. The house was burned down so no photographs were left, only an oil painting in three-quarters which I turned frontal. At that point I was also really impressed by the frontal imagery of Sandar, which is completely dishonest in a sense because it’s a posed image, so it’s a presumption or an assumption of somebody. There, I understood that every form of memory is completely inadequate, and its inadequacy is actually the sort of ambiguity that makes the visual into something interesting, because it actually works on different levels; it works on presumptions, it works on assumptions, and it also has an element of premonition within it. Those are all the uncertainties that pile up within the imaginative proposition of making an imagery, which is always layered—it’s not one layer, it’s several layers. That’s what makes it important, because it will make you doubt the imagery, and doubting an image is important because it works on your brain and it works on your memory.

There was a museum director from Honolulu who hated my work, and when he saw my show at the Tate Modern in 2004 he hated it even more, until he started to dream about it. Then he became a fan. Painting works through time, over time, with time. It’s a very specific slow medium in that sense.

In past interviews, you’ve talked about tonality and a sensibility to light that’s particular to the region of artists you come from. Can you develop on this?

As we look out of the window right now it’s mostly gray here, but the gray has a certain luminosity. I don’t live in California, if I lived in California or Spain the shadows would be different. So in that sense the luminosity is something that eventually always ends up in the tonality. Tonality is an uncertainty within how you perceive culture. Tonality, unlike pure color, creates depth, real depth in a painting, not just a perspective, but real depth in how you assess it, and that is probably to a certain extent linked to the region.

The Fruit Basket is your most recent work on view. Looking at the past 50 years, how has your work changed? Has your process evolved?

The process has changed continuously because we live in a different world. Already the light of the digital is interesting, you can’t get away with it.

When I was given the Max Beckmann prize at the Städelschule, I had to work with the collection, I had to talk to the students, give lectures, and make a big exhibition. I made an exhibition choice about the whole collection, which I showed, but I was also asked to put one of my works in the museum at a specific space. So I shared a space with Max Beckmann and Fernand Khnopff, The Game Warden (1883), because it’s a painting I remembered, and it was actually an image I thought would fit in well. But it didn’t because it was digital light. In a sense you cannot get away from the contemporary, you will evolve if you like or dislike it, it’s going to have an impact. I came to the conclusion that you cannot fight new media, that’s stupid because that’s a fight you can’t win, so it’s better to incorporate it into the toolbox, and in that sense of course things will change.

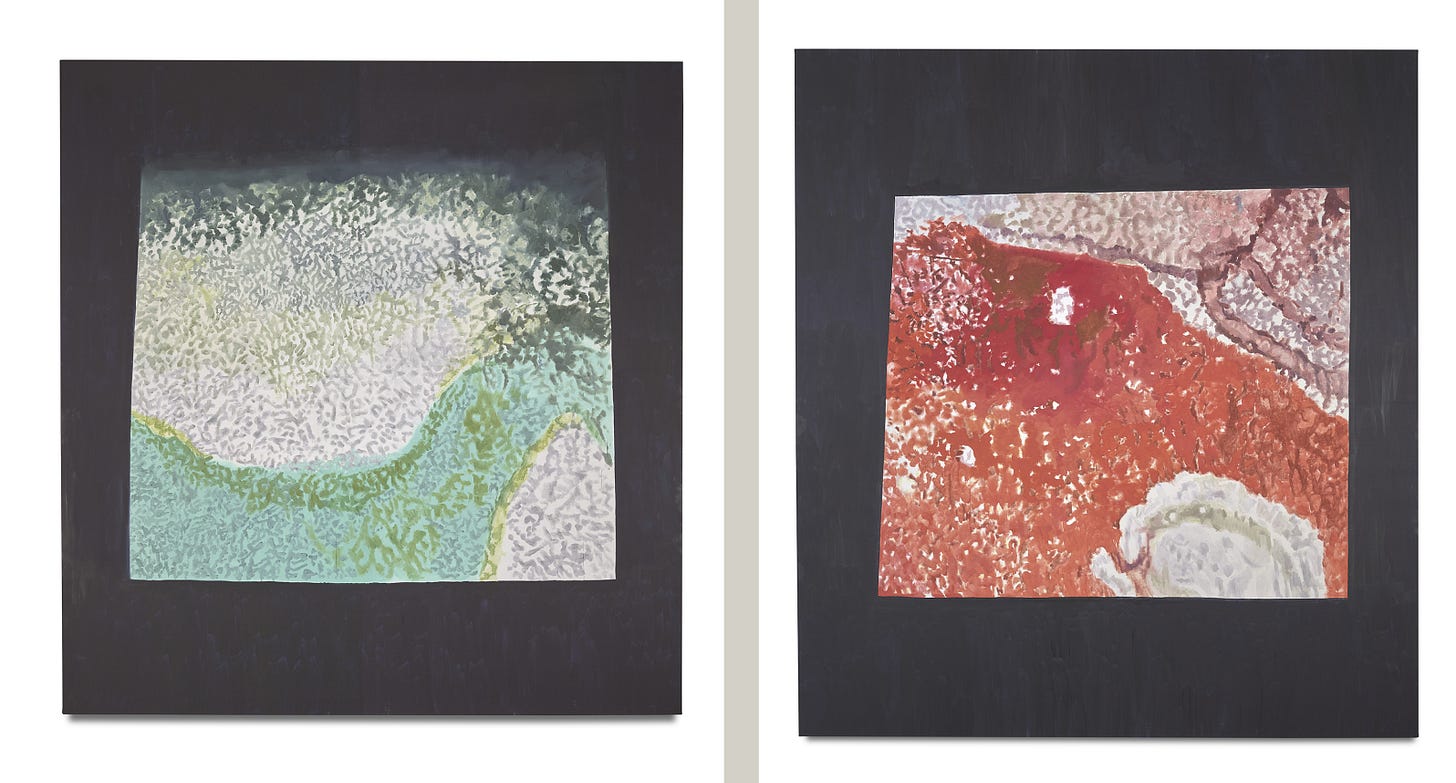

Now, with The Fruit Basket this is quite imminent, and also with the Illuminations in the show. We show very enlarged images with a sort of dark border that I painted around them, and the fact that they become parallelograms, they’re not really straight. You can see there that the light is enhanced. For the first time I was able to paint digital light. The same is actually happening with the 9-piece sort of The Fruit Basket that you see, so of course it changes continuously.

It took me a long time to assess the idea of quantas. I was always afraid of going over my contrast, so a lot of the imagery looked over-developed on the vanishing point, which is interesting. Now three years I enabled myself to use more color and also to go deeper into the contrast, but a long sort of trajectory to actually come to that.

What does this deeper contrast do to the work for a spectator?

It will make the work and its experience different.

It’s also interesting in museum shows to see—especially the big show I did in Beijing, The Past—how the size grew, how the touch, I mean the way how paint was applied became loose or different than the concise things in the beginning. Also the early works are now 40 years old and already retrieved themselves in a very different way. That’s an interesting juxtaposition, it’s something that’s not completely controllable but on the other hand it grows in a very organic way and has a logic of its own.

In addition to painting, you also have a curatorial practice.

I thought the curatorial practice was an interesting experience, to have to work with another artist’s work. I worked on a big show for China which was art from the 15th century in the lowlands in combination with old Chinese masters from the same time period until the 20th century, which was shown in the Palais des Beaux Art and in the Forbidden City. The second venue was together with Ai Weiwei, where we did contemporary Belgian and Chinese art.

The interesting part is that you can open up the situation to include young artists, which I find really interesting. In the other way, with the old masters, you can make a different point, you can make a different assessment, different worldview which you oppose. So it broadens the scope where you get the idea you’re not just only part of a market that’s a system which has become corporate. So it’s kind of a good antidote against that.

In your lecture, Curating the Library, you evoke three literary works: Spinoza’s Ethics, Life on Earth by Jan Jacob Slauerhoff and Ästhetik des Vorscheins by Ernest Bloch. What is the connection between these works and your thinking?

Spinoza was the last philosopher with a sort of closed system, which was then destroyed by Immanuel Kant. Nevertheless it’s a mathematical proposition of the world and the idea of the principal of God. I found, and still find, it to be not only beautiful but very valid in the sense of the rationale, of how you can look at the world.

Ernest Bloch was the philosopher of the possibilities. He was a philosopher in East Germany and this one book, Ästhetik des Vorscheins, on the aesthetics of appearances was interesting in terms of culture. He also has this one saying that between there’s nothing and nothingness is the process where something actually starts to exist, which I found a very interesting statement.

And Jan Jacob Slauerhoff, specifically that one book I read in an afternoon is very famous, he’s a cult figure in Holland. He was a writer, a poet, but also a writer of novels. He was also a ship doctor and wrote most of his books in different places like in Mexico, China, he also learned Chinese, and he was one of the inventors of the Nouveau Roman before it actually happened. He died in 1934 and made a very interesting statement where he said the world has become smaller in distance but very large in terms of psychology, and I think that was an interesting statement right before the second world war.

The Fruit Basket will be on view at David Zwirner in Los Angeles from February 24 through April 4.

Excellent questions and answers. I understand his sense of tonality in his work. While living in Zeeland in my twenties, I spent much time in Belgium.

Very interesting conversation