Finding yourself in a hole, at the bottom of a hole, in almost total solitude, and discovering that only writing can save you. To be without the slightest subject for a book, the slightest idea for a book, is to find yourself, once again, before a book. A vast emptiness. A possible book. Before nothing. Before something like living, naked writing, like something terrible, terrible to overcome.

— Marguerite Duras, “Writing”

The first time I read Marguerite Duras was ten years ago. It was her last book, a meditation on the process of writing, a gift from my husband who I’d only known for a couple of weeks. He lived in Paris and I lived in New York. I read it because I felt like I had to, because I was in love with him. I was consumed with desire, a longing for him, and I wanted this moment between us to burn inside me, I was entirely submissive to the choice he made for me. I’ll never forget that day. I propped a pillow up against the wall on my bed, it was a cold and sunny Sunday morning in New York when I started reading. For the next hour or so I wouldn’t come up for air. Duras took over, stole me from him and showed me what there was to be for a person like me.

When I see Duras in pictures or interviews I feel there’s only her, as if she was in my house. When I’m with her, I’m with her in her solitude. It all stops around me and I’m there in her room, her house, at night and during the day, in her madness, her sentences, with the women she writes into life. I see her, I love her like a lover would have loved her, it’s impossible to leave her, to let her be, to put her down, to forget.

There’s not a week I write when I don’t think about her words, her sincerity, her pain, her indifference, her becoming her person so she could write. I think of the silence she created for me and the madness I trail when I follow her steps. “To be alone with the as yet unwritten book is still to be in the primal sleep of humanity.” Wake up, WAKE UP she says.

Right now something called for her and I chose to listen, to read, reread, rewatch, feel again the solitude she brought into my life. She, who showed me the way to loneliness and silence, to the irreparability of pain.

It’s not by chance either that I’m always wanting to put women in houses, and no one other than women.

Novel

The Lover (1984)

I began the week at the end, with The Lover, her greatest success. Published in 1984, translated into more than 40 languages, adapted into a film Duras detested. The novel recounts the coming-of-age of a teenage girl in 1930s Saigon, then part of French Indochina. Living with her impoverished family, she starts a romantic affair with a wealthy Chinese man.

In many ways autobiographical, The Lover wasn’t the only time Duras drew from her own life. The Sea Wall, Eden Cinema, and The North China Lover do the same, as do most of her works. But The Lover feels uniquely porous, her life seeps through the text with particular urgency.

The story’s different from how I remembered it. The tense relationship between the girl, her mother, and her brothers is still there, and the affair remains central, but I realized Duras uses the man to escape something, to leave her childhood. So painful was life with her family, that only through this man could she find the pleasure and hope to live on, to learn about the woman she was and assume her individuality. The structure follows the girl’s flow, Duras carries us past her limits and then pulls us back again and again, like a wave. The narrative voice shifts, we have mostly an I, occasionally a she, but the tone remains steady, a beautiful and sincere confession.

The horror of the family is something that is deeply engrained in every house: the need to flee all these suicidal impulses.

Film

Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959)

Watching Hiroshima, Mon Amour after reading The Lover feels like falling asleep on Duras’s lap only to relive our greatest pain, her greatest pain. With restraint for words and a meticulous use of language, Duras still manages to say too much. How beautiful it is, she makes us feel without saying, without writing, her words are as dead as she, there is only pain, she surpasses language.

She wrote the screenplay for Hiroshima, Mon Amour for the French director Alain Resnais (who later directed Last Year at Marienbad). Resnais wanted to make a film about Hiroshima and approached Duras for the screenplay. It tells the story of a French woman’s love affair with a man in Hiroshima 14 years after the war. It’s a story about love, death, memory, and reconciliation. Duras was nominated for an Academy Award for her screenplay.

I have to mention that I was the daughter of a civil servant and that, throughout my childhood, all I did was move between places. Whenever my parents changed jobs, I changed houses.

Documentary

The Places of Marguerite Duras (1976)

I could never have imagined that a place could have such power, such force. All the women in my books have lived in this house. All of them. It’s only women who inhabit places, not men. This house was inhabited by Lol V. Stein, by Anne-Marie Stretter, by Isabelle Granger, by Nathalie Granger, but also by all kinds of other women. Sometimes, when I enter the house, a feeling comes over me, all of a sudden—the feeling of a profusion of women. This house has been inhabited by me, too. Entirely. I think it’s the place in the world I’ve inhabited most fully, and when I talk about these other women, I believe these other women contain a part of me, too. It’s as if me and these women, it’s as if we’ve been endowed with porosity.

Across the two hours of this documentary, we see Duras within the confines of her home, the property in the Yvelines where she was at her most prolific. We hear her talk about writing, about the house, about what it means to be a woman alone inside her home and in nature, in the park, in the forest. We witness the perilous image she keeps of nature, the violence she senses in it, the violence from her childhood, and the desire to escape, to propel oneself into the unknown.

The forest belongs to mad people, you understand, and in my life, the forest was childhood. It’s a forest of journeys, if you like – real journeys. But that’s childhood as well, you see. But not everyone in my books is scared of the forest…When I’m scared of the forest, it’s myself that i’m scared of, of course. You see, I’ve been scared of myself, since puberty, no?

Film

Nathalie Granger (1972)

Unlike Hiroshima, Mon Amour, Duras wrote and directed Nathalie Granger. In it, a mother and her friend feel a child’s violence seep into their home and into their lives. The violence saturates the silence of the house, haunts its rooms, just like it did Duras’s life.

It’s interesting to observe Duras’s relationship to music in this film, something I only grasped after listening to her speak about it in the documentary I mentioned earlier. She loves music but can’t bear to listen to it. As a child she could, but as an adult it becomes too much, too overwhelming. In the film, while the child practices her scales, the camera lingers over the scattered sheets of music spread across the floor, never touching them. Duras analyzed the scene in this way: “the distance covered here, from the scales of children, the scales of childhood, or the childhood of humanity, all the way to this language we can’t decrypt, the language of music—this distance overwhelms me.”

The first sign of life is a scream of pain. You know, when air first gets into the child’s lungs, the pain is unspeakable, and this is the first manifestation of life: pain. It’s a scream. More than a scream, you understand. It’s the scream of the slaughtered, the scream of someone being killed, assassinated. The scream of someone who doesn’t want it.

Novel

The Garden Square (1955)

When Samuel Beckett first heard The Garden Square on the radio, he called it “overwhelmingly moving.” The story unfolds as a dialogue between a girl and a man who meet for the first time on a bench in a public square. The only moments in which Duras uses narrative descriptions in this work is to describe changes to the weather—if the sun has come out from behind the clouds, if there’s wind—serving only to position each character’s experience with nature.

The girl is asleep, waiting for something to happen in her life. She’s incapable of experiencing the present, thinks only of the man she hopes to meet at the local dance hall, a marriage she imagines will jumpstart her life. The man is disillusioned by life, has accepted his fate, lost hope for change, and carries on travelling between cities and selling things no one needs to afford himself lunch. He can only think as far as his next meal.

Yet as they sit together, talking, something changes. We see them step into the present for the first time, unaware of the force their meeting holds. In that brief encounter, they share a moment outside their limits, one entirely at odds with the constraints that define them.

When I’m in that room, I don’t feel as though I’m disturbing anything of the room’s specific logic, as if the room itself, or rather the place hadn’t noticed that I was there, that a woman was there: she already had her place in the room. I’m talking about the silence of a place, probably.

Novel

The Ravishing of Lol Stein (1964)

She’s incapable of reflection, Lol V. Stein, she stopped living before the time of reflection. Perhaps that’s why she’s so dear to me, that I feel so close to her, I don’t know. Reflection is a tense, a time that I’m suspicious of. Yes. Which bores me. And if you look at my characters, they all come before this time, or rather the characters I love most. It’s probably the state that I try to get into when I’m writing, a state of intense listening, you see, but in its external form.

Lol V. Stein is a character who is completely haunted by the experience of S Thala, by the ball. It’s an ugly word, le vécu, experience, but what can you do. I don’t know what other word I might use. She’s haunted like a place is haunted. That’s Lol V. Stein, someone who remembers everything for the first time, everyday of her life, and this remembering is repeated every day, she remembers it every day for the first time. As if for Lol V. Stein there were these unfathomable chasms of forgetting between each day. She can’t get used to memory, or forgetting for that matter. She waits outside the casino, she is asleep on the beach, half dead. Her fingers are half buried under the sand, she has a bag next to her, a bag that I think looks like a little girl’s. She’s dressed all in white. Half dead, asleep. There, I see her, but alive.

There’s no sense to get from Lol V. Stein, you see, no meaning. Lol V. Stein is what you make of her. Without that, she wouldn’t exist. I think I’ve just discovered something about her, from what I’ve just said. She began to have a sense for me, a meaning, after she came from. After I came upon her, rather, you see...

Essays

Practicalities (1988)

In these essays, Duras is at her boldest. She is a woman, a woman in relation to a man, a woman in the house, a mother, a writer, an alcoholic, a provocateur, and unapologetically herself. Alongside Joan Didion, she’s one of the rare authors whose voice I hear clearly in my head with every word. Practicalities reads as a confession, a sequence of everyday thoughts and pure, unfiltered gossip.

“I became an alcoholic as soon as I started to drink. I drank like one straight away, and left everyone else behind.”

“You have to be very fond of men. Very, very fond. You have to be very fond of them to love them. Otherwise they’re simply unbearable.”

“One reason, perhaps the chief reason, why houses are flooded with material possessions is the longstanding rituals by which Paris is regularly submerged by sales, super-sales and final reductions.”

Film

Aurélia Steiner Vancouver (1979)

In Aurélia Steiner Vancouver, part of the Centre Pompidou’s permanent collection, Marguerite Duras revisits a recurring character in her novels through a letter she once wrote to her parents. She repurposes footage from an earlier film to build this work, and illustrates the mysterious story of the woman’s past.

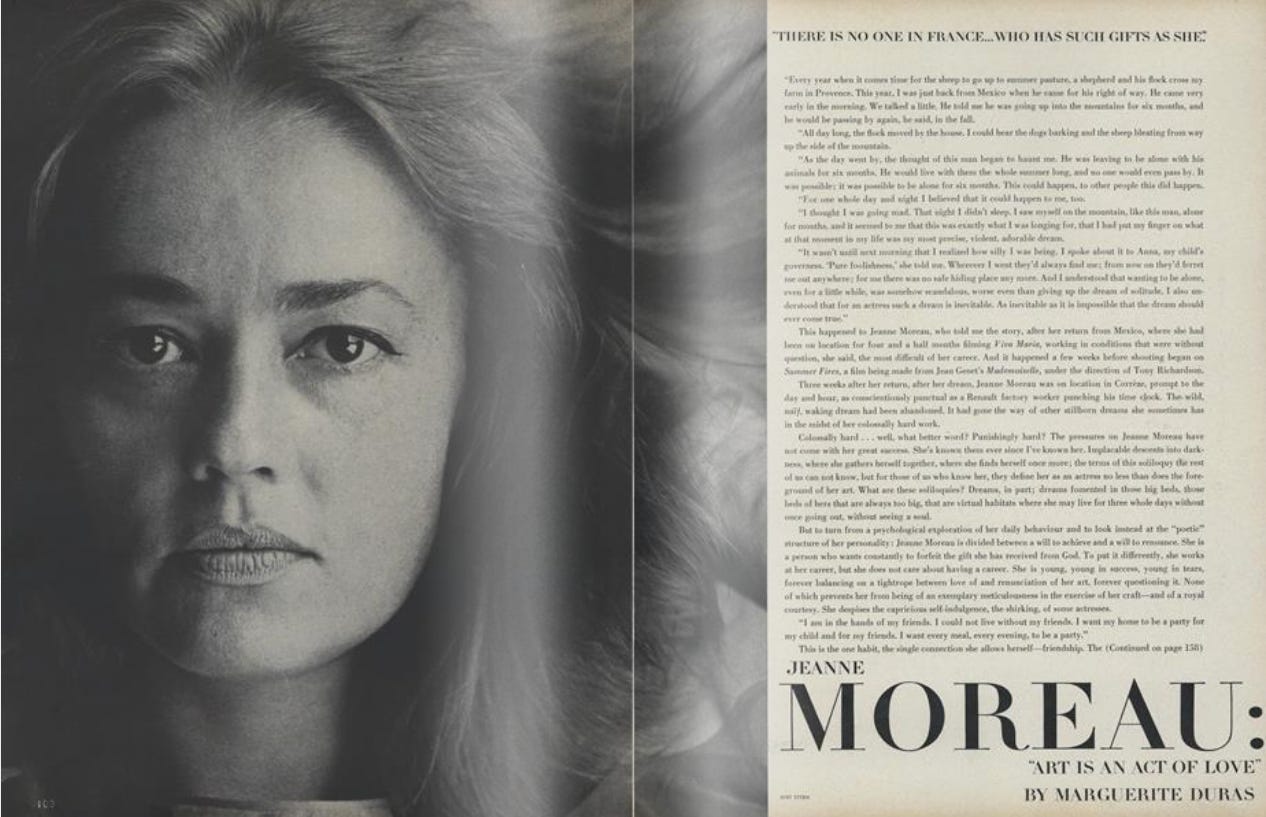

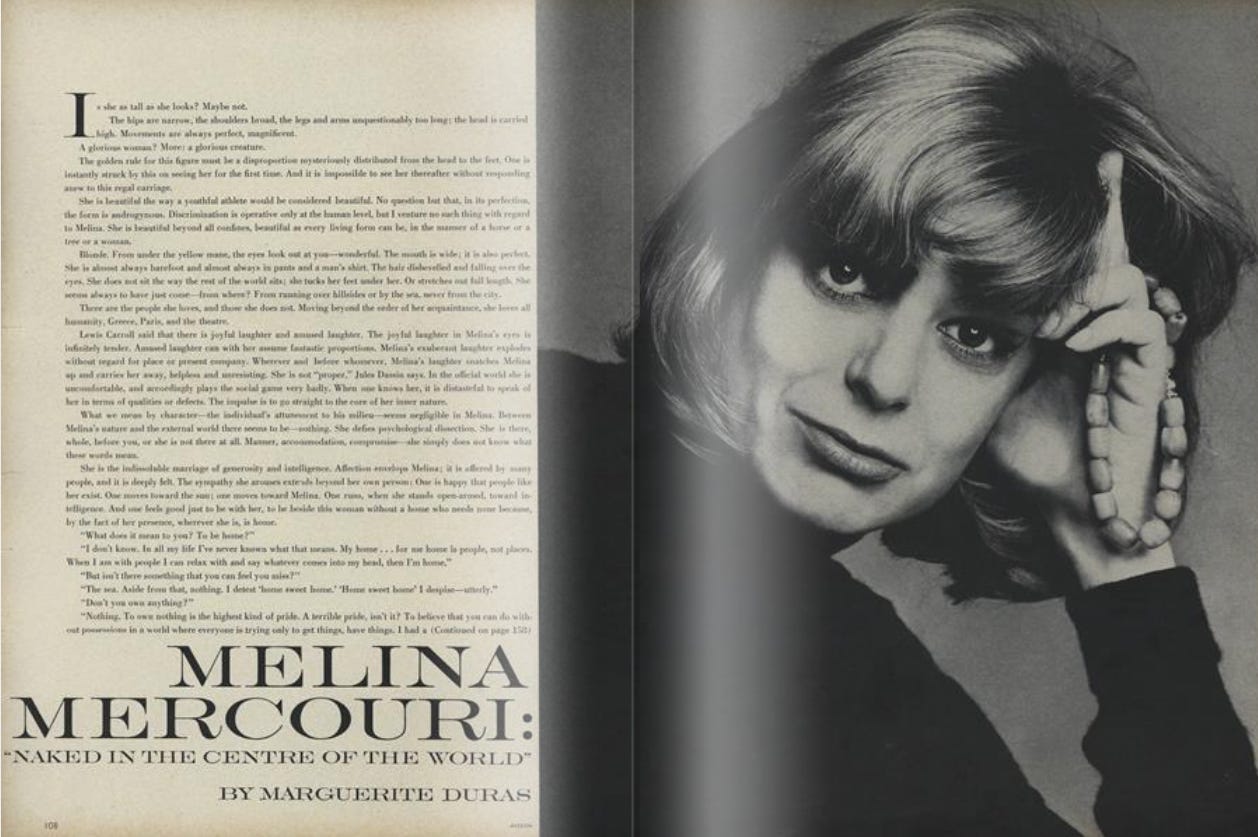

*Duras also wrote several profiles for Vogue. In the mid 60s she profiled Jeanne Moreau, Brigitte Bardot, and Melina Mercouri.

Additional Resources

Duras is my intruder. She arrived without asking and I’ll never let her leave again. I’ll continue to revisit her, as I have since I first encountered her. It would be impossible to let her go.

Here are some other books, films, and readings I recommend.

Books

There are more, many more. Duras was prolific. She wrote constantly, stopping only when she was making her films. She published over 40 books in her lifetime, burning each of her manuscripts once they were published. These are the ones I recommend. Her early works are less experimental and I’m less interested in them, but I’ve never read them and in not doing so could not opine.

Moderato Cantabile

The North China Lover

The War: A Memoir

Emily L.

Blue Eyes, Black Hair

L’homme Atlantique

Détruire Dit-Elle

The Malady of Death

Suspended Passion

Me & Other Writings (Summer ‘80)

Film and Theatre

India Song

La Femme du Gange

Jaune le Soleil

Essays and Articles about Marguerite Duras

Edmund White writes In Love With Duras for the New York Review of Books in 2008, where he also reviews her books The North China Lover and The War: A Memoir.

Michel Foucault talks with Hélène Cixous about Marguerite Duras in Cixous’s book White Ink: Interviews on Sex, Text and Politics.

An essay by the historian and film critic Robert P. Kolker on Duras’s films, The Cinema of Duras in Search of an Ideal Image in the 1989 French Review.

A 1961 article by Jacques Guicharnaud, Woman’s Fate: Marguerite Duras, in the department of French studies at Yale.

The Life and Loves of Marguerite Duras, a 1991 article in the New York Times by Leslie Garis ( she also profiled Georges Simenon, Rebecca West, John Fowles and Harold Pinter)

If you can understand French, RadioFrance did a piece on Duras in 2019.

A wonderful summative reflection on a singular writer. Since the first time I read The Lover, I have been haunted by her language. In The Lover and in Hiroshima Mon Amour, her capturing or maybe better, her generation of the the broken, gap-ridden rupture of trauma in language has remained with me since I first encountered it many years ago now...

Gosh, I am so thankful I have found your substack. This is breathtaking, especially the introduction.