In Conversation with Nicolas Trembley, Finding Meaning in Forms

The Swiss curator bringing new typologies into the arts.

IN CONVERSATION WITH

Nicolas Trembley

Interview with Nicolas Trembley by Renata Mosci Sanfourche

Nicolas Trembley’s allure lies in his commitment to questioning certainty. The exhibitions he curates invite viewers to abandon inherited cultural hierarchies, reconsider how value is assigned in the arts, and open spaces for richer, more complex exchanges in culture.

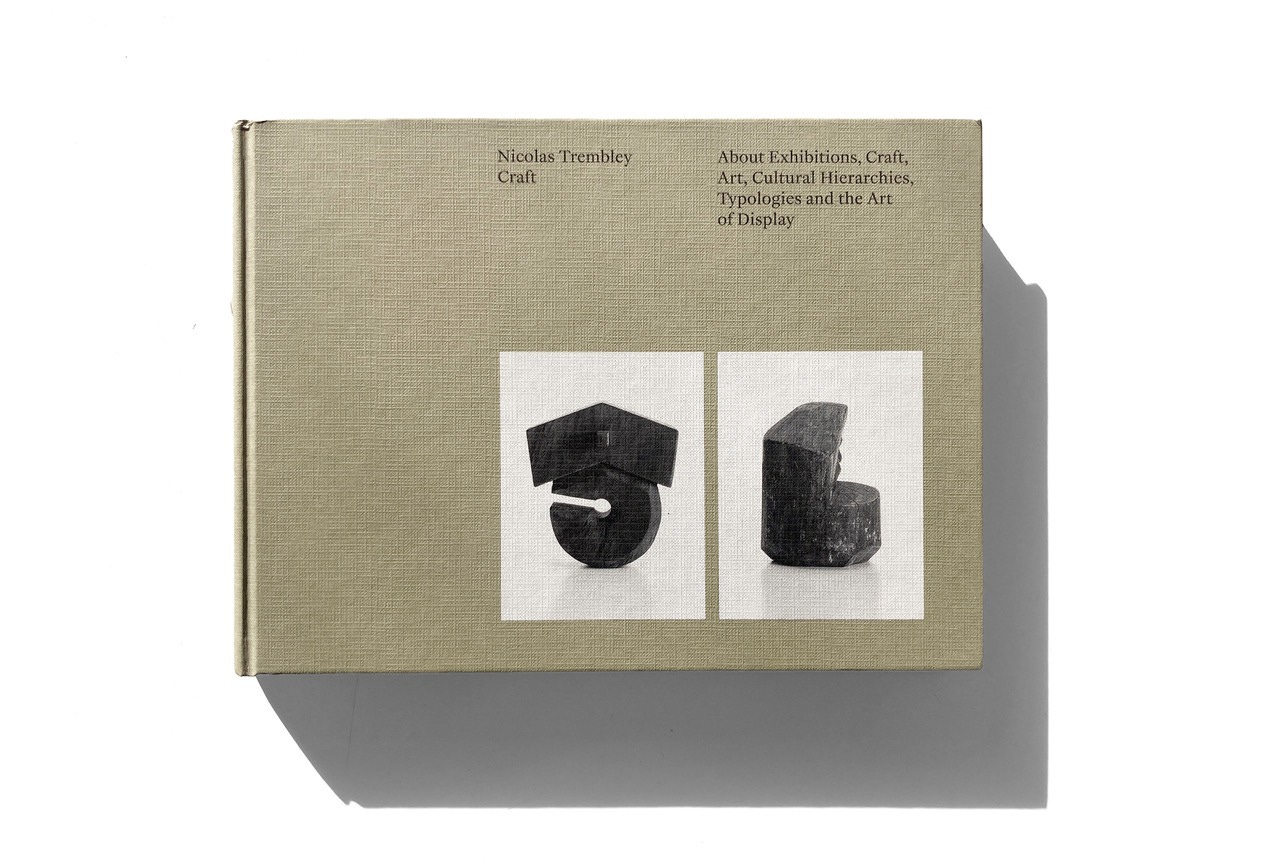

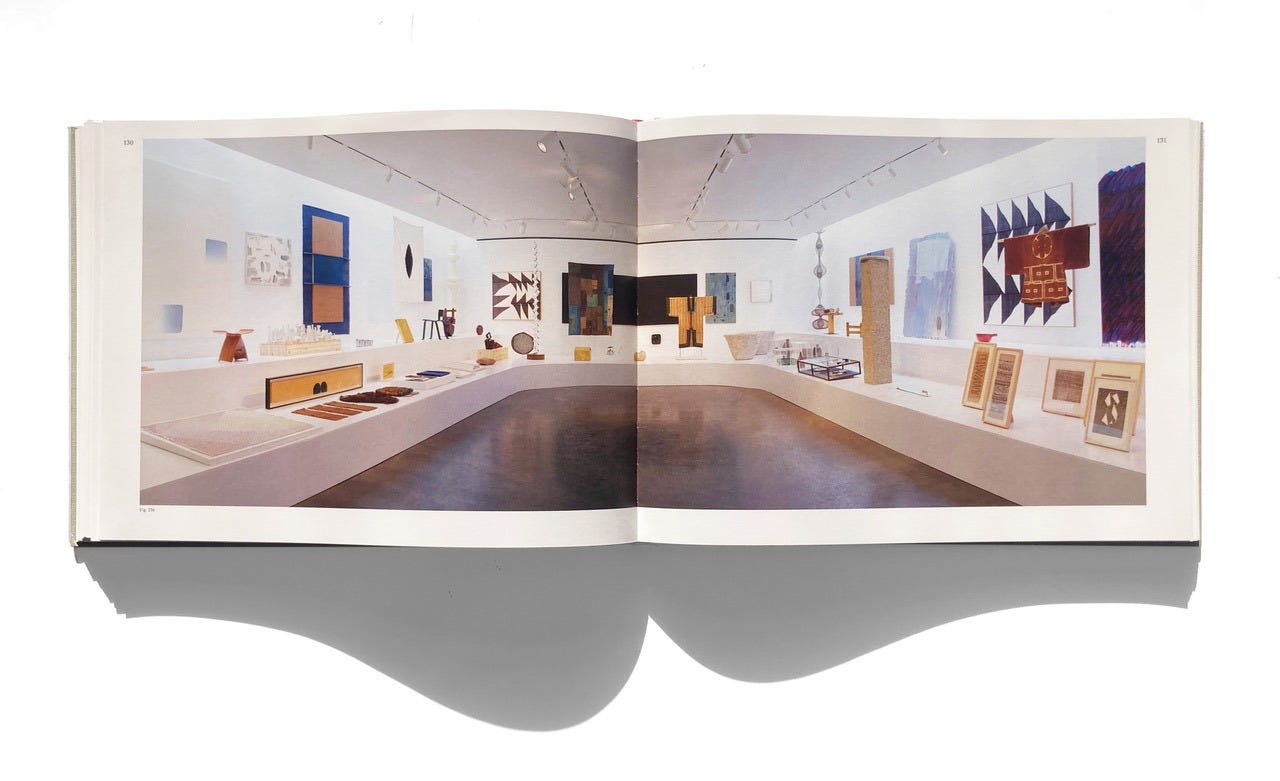

For over a decade craft has been central to Trembley’s practice. His meticulous consideration for their display, installation, and presentation are in itself worthy of close study. Through his exhibitions Mingei: Are You Here? at Pace Gallery and Craft at Galerie Francesca Pia, he interrogates art history’s Eurocentric vision, framing non-Western vernacular traditions not as relics of the world’s past, but as renewed practices in contemporary art.

Through his research and numerous exhibitions, Trembley challenges boundaries to make room for new typologies in the arts, proposing time and again a critical rereading of the canon. His most recent book, Craft, published Tuesday in Paris by After 8 Books, offers insight into his working process and philosophy through a dialogue with fellow curator Véronique Bacchetta.

You are concerned with breaking hierarchies in the art world. Where do you see yourself as a curator within the institution? Do you consider yourself an outsider or an insider, and what responsibilities accompany this position?

I see myself somewhere in between. I’ve worked inside institutions and with galleries, but always with a desire to question their frameworks and hierarchies. I don’t believe in the simple insider/outsider dichotomy. I’m close enough to understand how the system works, and distant enough to challenge it. This position comes with a responsibility to create spaces where marginalized forms such as craft, vernacular practices, or utilitarian objects can be seen and understood differently.

How does Ursula Le Guin’s 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction align with your beliefs?

What I find compelling in Le Guin’s essay is that she proposes a completely different kind of narrative, one we could easily apply to art history. She challenges the traditional point of view, which has historically focused on heroic, often male-oriented stories: wars, conquests, geniuses, masterpieces. Instead of this linear, monumental structure, she suggests using the metaphor of a carrier bag as a container in which we collect many different kinds of stories.

This carrier bag allows us to hold together narratives that are usually overlooked, the minor, everyday, practical gestures that enable a community to live; gathering, making tools and cooking vessels, repairing things. These stories are generally treated as secondary, yet Le Guin shows they are just as foundational as the grand mythologies of heroes and battles.

This idea of a narrative made from a collection of diverse, modest elements, resonates strongly with my curatorial practice and with the title of the exhibition. It expands our understanding of what is worthy of attention. Rethinking narrative through this lens allows us to challenge the dominant conventions that elevate certain forms and marginalize others, in art as much as in literature or society.

In a 1985 interview for Artforum, Anni Albers said about weaving “I find that, when the work is made with threads, it’s considered a craft; when it’s on paper, it’s considered art.” It’s a very interesting observation on the hierarchies in art.

What makes something a craft and what makes something art? What role, beyond the work itself, does a craft artist need to play to challenge these institutional frames?

Anni Albers’s remark reveals how constructed and arbitrary artistic hierarchies are. Craft is often what comes from domestic life, utility, or illegitimate traditions, while art is what institutions decide to elevate. For craft artists, challenging these frames sometimes requires adopting institutional codes; writing, theorizing, and performing a public identity. Part of my work is precisely to dismantle these barriers and invite other forms of legitimacy.

But it is also, for many makers, a matter of choice. The choice of whether or not to position oneself as an artist. Some people are interested primarily in technique, in perfecting a gesture or mastering a tool. Artists, generally, worry less about technique for its own sake, they use it as a means of expression rather than an end. And yet, reading Anni Albers’s numerous writings on weaving, tools, looms, and techniques, it becomes clear these reflections are an essential contribution to 20th-century (abstract) art. Her work demonstrates technical inquiry and artistic thought are not opposed but can mutually reinforce one another.

Your work is also concerned with transcending time, style, and form. How important is the role of the curator in defending a work when the artist is no longer alive?

When an artist is no longer alive the curator becomes an essential mediator. We must avoid two traps: over-interpretation and fossilization. My role is to place works into new conversations, connecting them with other objects or practices so they remain alive and relevant in the present.

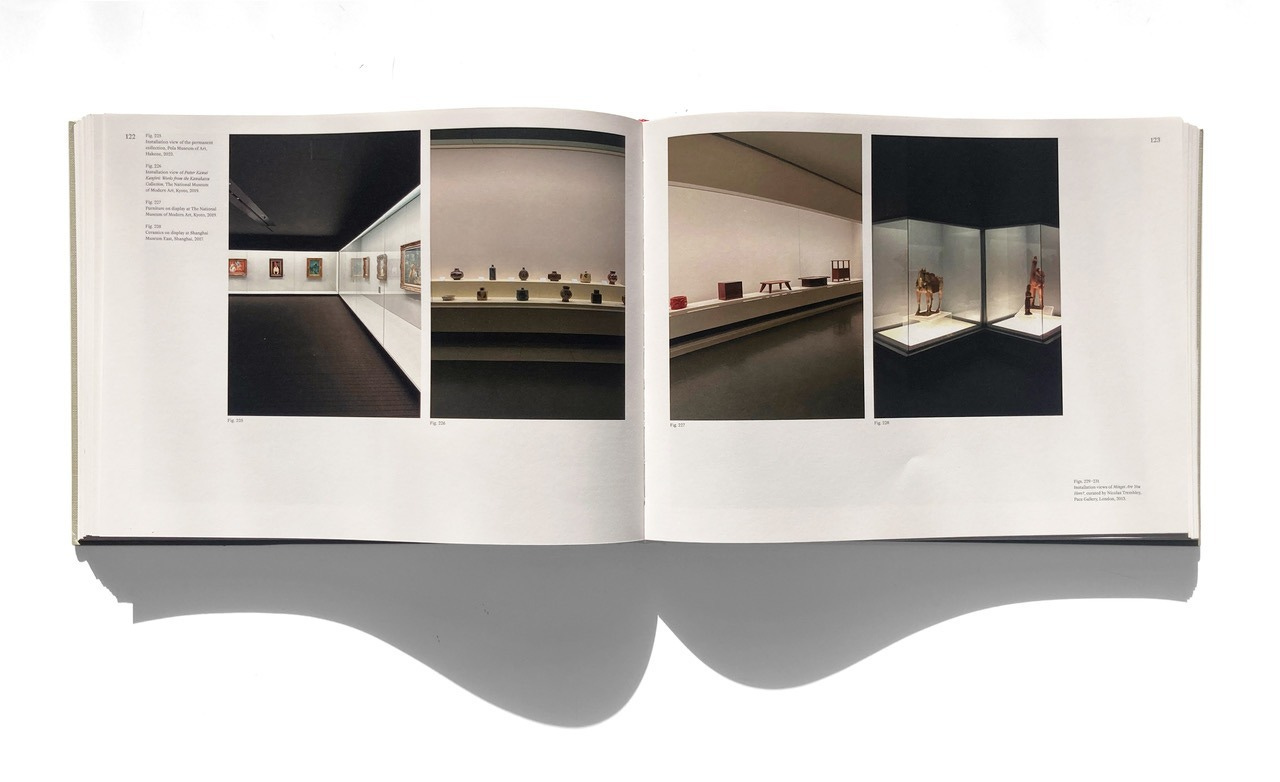

I find it particularly interesting to confront objects or artworks from the past with contemporary art, because it breaks the linear narrative we were taught. Display can disrupt chronology and create new ways of reading history. I often think of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, which I visited to inspire some of my own projects. When Pitt Rivers donated his collection to the University in 1884, he stipulated that the objects should be preserved and displayed in a specific way; grouped by use or function rather than by geography or culture.

This typological approach—placing weapons from different societies together or domestic tools side-by-side regardless of origin or date—creates a fascinating system. Chronology disappears, and what emerges instead are shared gestures, forms, and needs across cultures. This method offers a powerful model for thinking about juxtapositions today, it shows how objects from different times can resonate with one another, it allows the past to speak with the present in unexpected ways.

When you talk about “Mingei Are You Here?” the exhibition you curated at Pace Gallery, the principle seems to take precedence over the object itself. You even say other series of objects could have replaced Mingei and the exhibition would’ve been the same. What do you mean by this?

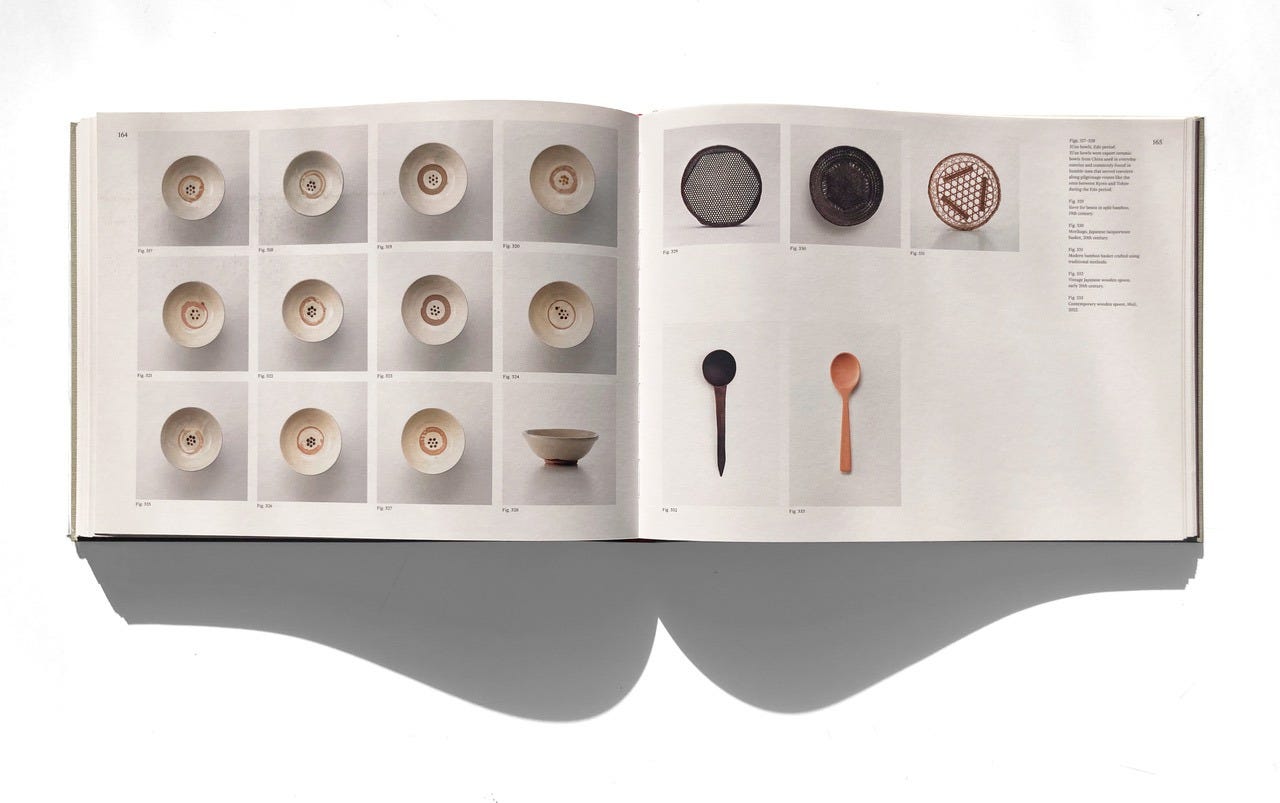

It’s not entirely accurate to say the principle is more important than the objects. I have a deep fascination for Japan, for its aesthetics and cultural objects. Mingei is a very particular movement because it forces us to look at things that were never meant to be looked at, objects considered minor or insignificant. I often think of something as simple as a wooden spoon carved by a farmer. Mingei invites us to recognise beauty and meaning where the canon historically saw none.

This philosophy, which radically overturns the aesthetic hierarchies we were taught, was already close to what I wanted to do when I showed so-called kitsch German Fat Lava vases. All it takes is to look at them differently and change their context—for example, removing them from the doily on top of the television set (before flat screens) and placing them in the white cube of a gallery—for the object to become visible in a new way.

So yes, the underlying approach is important, but not more important than the objects themselves. When I say that other objects could have replaced Mingei, it’s true, I recently tested this idea with vernacular Provençal furniture in the French Mingei exhibition in Kobe, and the method worked. What I meant is that there are many possibilities, many other fields still to explore. Mingei is one example of how we can challenge established hierarchies, but it’s far from the only one.

In your interview with Véronique Bacchetta for your new book Crafts you say, “art, architecture, and design develop cyclically, influenced by trends, tastes, as well as the ethical and economic values corresponding to every era.” What are these values today?

Things are changing, and when we see large international exhibitions presenting works by artists we did not previously know—often from communities or minorities that were long unfamiliar to the Western canon—it means the shift has already begun, and this is undeniably a positive development.

For decades, the financial art market was almost entirely dominated by works made by white, Western male artists. To some extent, this is still the case, but the margins have moved. We now see ceramics by Magdalene Odundo or textiles by the Gee’s Bend quilt-makers reaching prices completely comparable to those of painting. This evolution shows the values of our era are expanding: the center is no longer fixed, and forms once considered peripheral are finally receiving the attention and legitimacy they deserve.

The first definition of the readymade came in 1917 by Marcel Duchamp. He said “whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, and placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

Before Duchamp, Henry Moore was collecting bones and flints and showing them as found objects. Your work develops from a found object but is transformed in its collection and display. How do you relate to these ideas?

I feel very close to these ideas; it is always stimulating—and often amusing—to question the dogmas that structure the art world. I would like to cite a reference that was crucial for my own research on objects: the exhibition Raid the Icebox that Andy Warhol created in 1969 with the permanent collection of the RISD Museum. I still consider it one of the most subversive proposals ever made on display and on the notion of artistic value.

Raid the Icebox was initiated in 1968 by Jean and Dominique de Ménil. During a visit to the museum’s storage with Daniel Robbins, the director at the time, they agreed to invite an artist to propose a new vision of the permanent collection. Warhol responded in a radically provocative way: he moved entire sections of storage directly into the galleries, disregarding the objects’ condition, value, or even their authenticity or canonical status. Everything was exhibited, rococo paintings, sculptures, hat boxes, umbrellas, furniture.

The show, nearly sixty years old now, raised sharp, complex questions that remain absolutely contemporary: how and why do cultural institutions construct hierarchies, whether historical or aesthetic?

My relationship to the readymade emerges in this context. I am interested in found objects, but not simply in choosing them, rather, in how they can be reorganized, recontextualized, and displayed to produce meaning. It is in this shift from the isolated object to the system of presentation that I locate my own position in relation to the ideas of Duchamp and Moore.

How does a collection of objects transform the perception of an isolated object? How do the values of seriality and repetition we saw in the minimalist movement play a role?

I began collecting objects at the same time I started building a contemporary art collection for the Syz family. It allowed me to test possibilities and explore how meaning shifts when objects are grouped rather than seen individually. The question of the series was essential. It’s a bit like the game of Seven Families: some series share the same shape, but vary in size and color. If you manage to gather the whole set, the collection feels complete. But if you’re missing even one element, you can spend your entire life searching for it… and that search easily becomes an obsession.

A single object can be anecdotal, many objects become a narrative. Seriality reveals variations, forms, and gaps that only appear through repetition. This is something I have always appreciated in minimalism: its ability to make visible what would otherwise remain unnoticed.

I also try to avoid what I would call the atomization of a collection, having “a bit of this and a bit of that.” When a collection is coherent, when its internal logic is visible, it becomes much stronger. The relationships between the objects intensify and their meaning expands.

I am very drawn to systems of classification, to serial logics, to the mechanical rhythm of repetition, but also to the differences contained within similarities — the kind you find in natural history museum vitrines filled with beetles, or in the aisles of screws at the BHV department store. I am a fan of industrial design that advocates quality for the masses, and I have always been fascinated by atlases and their encyclopaedic ambitions.

Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas has been a major source of inspiration. In 2020, the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin reconstructed the 63 historical black-velvet panels of the Atlas, with hundreds of his thumbtacked images. Warburg juxtaposed Renaissance frescoes with Etruscan symbols, newspaper clippings, postcards, maps, sports photography, or Hopi ritual documentation. The panels suggest connections and leap across time and space, functioning almost like a contemporary mood board where periods, styles, and forms intermingle freely.

Such arrangements create new links and interpretive possibilities that disrupt canonical systems of knowledge, making them richer and more complex. This philosophy deeply interests me, informs my projects, and is something I continually strive to apply in my exhibitions.

How do you build an environment for the display of crafts in the context of your philosophy? Is it important for you to show in galleries over museums?

I would actually love to show more in museums, but the temporality is very different. Galleries are more reactive, and of course the objects are often for sale, which creates another kind of flexibility. But my background is in museums. I studied anthropology and sociology, not art history, and this has shaped my entire approach to exhibitions. Over time, I became more interested in texts dealing with the ethnography of the cultural field and with the museum as one of its central tools of transmission.

I studied with the ethnographer Georges Balandier, and we reflected on Jacques Maquet’s The Anthropologist and Aesthetics, Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy, and George Kubler’s The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things. In sociology, I had Edgar Morin as a professor. With him, we looked at cars, film, fashion, exhibitions, all through a transdisciplinary lens, exploring how different forms of knowledge intersect. We also read Stuart Hall on the deconstruction of the popular, and of course Pierre Bourdieu on the correlations between aesthetic taste and social structures.

You talk about applying the principles of ethnography to museology. Can you elaborate on this concept?

All my studies have profoundly influenced the way I think about display. In the earliest experiments in museology, exhibitions often contained objects rather than what we now call artworks. Curators at the time had to invent strategies to elevate these objects, to make them as desirable or as significant as the fine arts. This led to display methods that were far more inventive and exciting than those of traditional museums.

For me, this is where the principles of ethnography meet museology. Early ethnographic museums understood that context, juxtaposition, and narrative could transform the status of an object. They created environments that gave ordinary things a new visibility and a new dignity. This approach continues to inspire me.

Designing an exhibition is thrilling — it is like creating a stage for objects, a mise-en-scène that allows them to speak, reveals their relationships, and gives them a new presence. Whether in a museum or a gallery, the challenge is the same: to imagine a display that elevates and recontextualizes objects so they can be seen in ways they never were before.

In my first interview in this series I spoke with Desiree Heiss and Ines Kaag. I noticed you curated the exhibition for BLESS No 65 Not That I Can’t Wait For it. How does your world collide with theirs?

I admired the way they disrupt the canons of fashion—the runway, production systems, even the idea of the brand—and how fluidly they move between design, art, and other fields. Their work occupies a space in-between, which is exactly the territory that interests me.

When we organized the exhibition in a gallery in Paris, the vitrine was arranged like an apartment, a domestic environment rather than a conventional display. The subtitle of the show, Constantly Challenging the Norm to Encourage New Perspectives, felt absolutely right for them. They were initially reluctant to do an exhibition, because they tend to question every context in which they are invited to participate. I remember that they even intervened in the exterior of the gallery, extending the project beyond the expected boundaries.

Their approach consistently pushes against established formats, and that is precisely where our worlds meet.

What’s your perspective on Ruth Asawa, her work, and the late interest the art market had for her?

I am very happy that Ruth Asawa’s work is finally receiving the recognition it deserves on the market. It is, of course, sad that she is no longer here to benefit from it. I remember when we showed her work for the first time in Mingei Are You Here? at Pace Gallery, it was one of the pieces with the highest insurance value, around one million dollars if I recall correctly. Everyone thought it was absurd at the time. And today, Zwirner sells her works for twelve million…

The problem in the art world is that context often shapes perception far more than quality. Some collectors assume if a work is expensive it must be important, which is absolutely not true. Many expensive works will never change anything in art history. That is not the case with Ruth Asawa. She is a locomotive, and she will pull behind her many other works and practices of a similar nature.

This is wonderful, because it will give far greater visibility to forms — especially craft-based, non-Western, or historically marginalized ones — that much of the art world has ignored until very recently.