What’s a Chronicle Anyway? + Björk Interviewed Ocean Vuong

A voice recording shows László Krasznahorkai's reaction to winning the Nobel Prize, a brilliant essay by James Marriott, and more.

In this week’s newsletter: nine articles I recommend including an interview by Björk with Ocean Vuong (and one by Bella Freud), an essay about Mrs. Dalloway for the LRB, a community library Solange Knowles started, and more. A visual library, some books and a film my family’s into on their down time, and a podcast about Simone de Beauvoir.

Chronicle

What’s a Chronicle Anyway?

A long time ago in New York City, I dated a writer who kept associating me with Clarice Lispector, particularly with her crônicas. Not because of my work, but because we were both Brazilian women (except she was born in the Ukraine, I was raised in America). Each time he asked me what I was working on, I fluttered, wavering between the stories I was writing at home and some sort of cuticle cream article I was working on for the paper.

It was hard for him to imagine how a girl writing backstage beauty reports for the fashion desk could aspire to write anything other than the latest trends on mules, and I think he leveraged my ambition into something obvious for me to do: follow in Lispector’s footsteps by going where she left off, to chronicles. Everything about this annoyed me. I didn’t need to be prescribed a genre, I didn’t need him telling me night after night, over rounds and rounds of gin and tonics, that this was how I’d make it. I would’ve needed someone who believed in my capacity to find the right symbols for my thoughts and to turn them into something new. If I didn’t do this work I was going to shrivel inside, I depended on my ability to understand myself through words.

Years have passed since, and Lispector’s chronicles are now safe and out of exile (yes, I put them away for a long time). When I started conceiving this newsletter, and the type of stories I was willing to share, the New York writer, the guy who sat alone at skater bars reading Homer and telling me what to do, came briefly back to mind. I finally came around to the chronicle, but out of my own will and in my own way, all while keeping the round-ups I had become better at creating, and the short stories I worked on quietly at home.

A chronicle (as I’m calling it on my newsletter) is a literary genre where writers use poetry and fiction tools to recount a reality. They’re often published as weekly columns in newspapers, except chronicles are to newspaper columns what op-ed pieces became to objective journalism. Or what the New Yorker’s stories in The Talk of Town would be if writers were offered more creative freedom.

In the late nineteenth century, chronicles in Latin America became somewhat of a phenomenon. Many newspaper editors invited writers to break from the daily news with a weekly chronicle. Gabriel García Márquez wrote several political chronicles, as did the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío, the Cuban José Martí, and the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges.

What distinguished Lispector’s and Márquez’s chronicles from the other writers, and from the other pieces in the paper, was their take on the truth. Márquez believed embellishment was sometimes necessary to help convey the truth: “If to speak the truth you need to add one more tear, then what’s the problem?” he said to one of his students. He built on existing realities with his own truths, turning objective material into subjective, and some times fictional work.

Take for example the chronicle Márquez wrote about the Colombian man who survived a shipwreck. The editor didn’t believe he could add anything to a story the paper had already successfully covered, but Márquez insisted on speaking with the victim, and when he returned the next day with a four-part series that shared a colorful, detailed survival story, the paper’s sales grew tremendously.

It always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there’s not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality. The problem is that Caribbean reality resembles the wildest imagination.

— Gabriel García Márquez (1981)

If chronicles are an extension of a writer’s work, daily insight into their perspective, and a way for readers to fix the author onto their imaginations, then the writer really is the greatest character of all. To me, it is only by reading all of Lispector’s chronicles that we can begin to understand the woman who invented the protagonist G.H., who eats a cockroach in her maid’s bedroom.

The same phenomenon we see in Márquez’s approach to the chronicle, we also see in Lispector’s, except she went further. She had a great desire to dissociate from the form, to create something that could really obfuscate the author by blurring the truth, hiding what’s real with the unreal.

In an early piece from June 1968, she wrote: “Is the crônica a story? Is it a conversation? Is it the summation of a state of mind?” Three years later, in May 1971, she mused, “Let’s be honest: this isn’t a column at all. It barely is. It doesn’t fit the genre. Genres no longer interest me. Mystery interests me. Do I need to have a ritual for mystery?” This is exactly what the crônicas became.

— Jared Marcel Pollen in The Yale Review

Her chronicles read like an unrepentant confessional, her language is opaque and it’s impossible to understand why. That’s the beauty in them, what makes them even more relevant today. In a 2017 article for The Paris Review, Gabrielle Bellot positions chronicles in our current media landscape, “There is a pressing sense that we need definitive, well-sourced reporting to combat propaganda—including that of the current administration.” Bellot is referring to the early days of Trump’s administration and the rise of fake news, a time that gave rise to op-ed columns, a tool used by the media to heighten emphasis on its objective and factual content. “Partly because of this, some critics have declared that the confessional, as well as the personal essay more generally, no longer should define writing in the era of Trump,” Bellot continues. She goes on to refer to an essay Jia Tolentino wrote in The New Yorker where she comes to condemn personal stories, “individual perspectives do not, at the moment, seem like a trustworthy way to get to the bottom of a subject.”

How impersonal and withdrawn can anything we write be when we’re all our each accumulation of our experiences. The truth in all nonfiction is inherently fraught. Our columns, our reported pieces, our essays, what we call factual, rely on our personal failures as much as they do on our successes, they’re founded on our individual perspective, whether intentional or not. To this idea, Lispector’s and Marquez’s confrontation with the truth becomes liminal both to the arts and to the many forms of nonfiction narratives.

As much as I wanted to call my writings on here chronicles I thought I couldn’t. I couldn’t find my chronicles in their crônicas. The period in my life from which I extract my realities hold more time than Lispector’s and Márquez’s, and it is after all the chronicle’s proximity to the present that allows them to exist in the paper. What’s more, my memory can’t be a reliable source even when I’m telling the truth.

Although my use of time separate me from their chronicles, I still share something primordial with them as cronistas. I need a place to hide. I live with apathy toward telling the truth, I’m not capable of confessing like Neige Sinno and Edouard Louis. Perhaps because it’s impossible for me to know this truth, perhaps as much as I search for it I still won’t find it, perhaps I need to keep the real and the unreal colluded. What I’m sure about when writing this newsletter is the process, that like Lispector I can discover something new when I’m writing it. This is the freedom this newsletter purports to give me. There are truths that are easy for me to share, there are others that are secrets I cannot reveal, what I make of all of this is what I like to call chronicles.

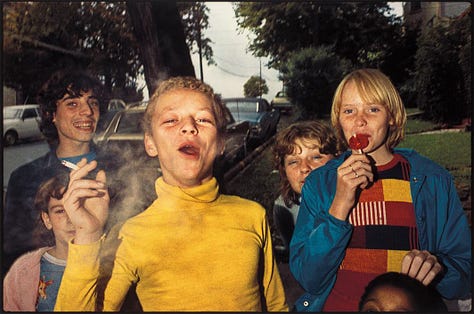

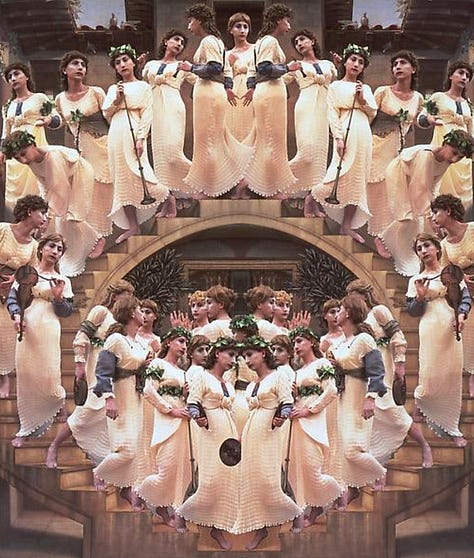

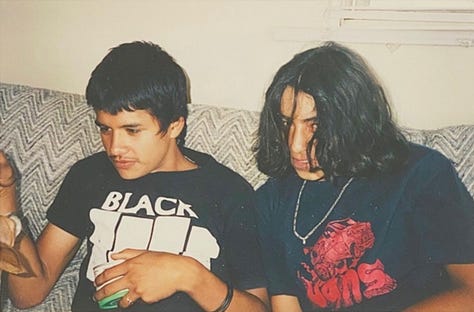

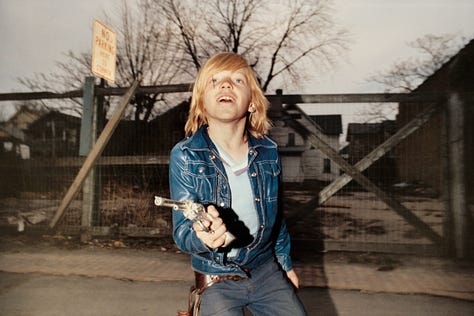

The Visual Library

Currently at Rue de Chabrol

Nine Articles I Recommend This Week

Solange Knowles launched a digital library, Saint Heron Community Library, that gives people access to an important roster of literary works. The library process is entirely digital, which is in itself a brilliant idea. People can reserve and check-out physical copies of these works for free and have them mailed to their house. Beyond making reading even more accessible, what stands out about this project is the titles Knowles curates and emphasizes as required reading. There’s great education to be had in a curated library. (Lithub)

The Yale Review is collaborating with the French bookstore Shakespeare & Co. to publish transcripts from conversations they host with international writers. Guests have included Abdulrazak Gurnah, Sheila Heti, Emmanuel Carrère, Ottessa Moshfegh, and Catherine Lacey. The first collaboration launched with Neige Sinno, author of Sad Tiger, an autobiography about the abuse she suffered as a kid in the hands of her stepfather.

When I studied literature, I wasn’t interested in autobiographical genres. I didn’t think that would be the path for me. For some strange and unconscious reasons, I convinced myself, later in life, to do something I hadn’t wanted to do in the first place.

— Neige Sinno

I didn’t read BOMB Magazine until someone sent me an article from their September issue where Björk interviews Ocean Vuong about his new novel The Emperor of Gladness. Who was the brilliant person that thought of this? I didn’t know they were friends! I also didn’t know Björk took weekly qigong classes. What emerges is a conversation about the simplicity of experiencing life without conforming to the pursuit of the American dream, being present can be fulfilling enough, no grand narrative arc needed, neither in the book nor in real life.

I wanted to write about kindness without hope, where people know that kindness will make no significant change in their lives and yet they commit to it anyway.

— Ocean Vuong

Bella Freud also had Ocean Vuong over on her podcast Fashion Neurosis.

David Trotter writes about Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway for the London Review of Books. He looks at the ways in which academics are celebrating the centennial of this particular novel (through four publications each offering a new reading of Woolf’s masterpiece).

A few weeks ago I told you Garth Greenwell was teaching an open course on Augustine’s Confessions. Last Friday, in his most recent newsletter, Greenwell gave us a taste of what sitting in that class might be like. His reading is detailed and pointed, he goes down to the bone. He looks at Augustine’s work and intention, at all its entry points, examines its construction in detail and extracts the parts that make us think differently not only about the work itself but about our own approach to writing.

This is the characteristic move of the Confessions: Augustine is constantly trying to turn around to face the self, to catch the self out, to investigate anything we might take as given about ourselves. Augustine can never merely think a thought or feel a feeling: he has to examine the act itself of feeling and thinking. He has to figure out everything, especially the most obvious things, from scratch. He has to become a problem for himself.

— Garth Greenwell

I got a teaser on Instagram for Rosalind Krauss’s October Magazine issue 191, for the essay Women on Walls: Projection, Anonymity, Envy, and Eileen Gray by the culture theorist Anne Anlin Cheng. I haven’t received my copy yet, all I can tell you is Anlin Cheng will be analyzing a collage made by Eileen Gray:

I bring to bear on Gray’s collage two other, seemingly separate stories, each with its own secrets and surprising revelations—Melanie Klein’s work on reparation and the creative impulse, on the one hand, and Le Corbusier’s fraught relationship to Gray’s architectural creation E-1027 on the other—and trace how the specters of female creativity, Baker, and racialized femininity haunt all three. By triangulating Gray, Le Corbusier, and Klein, we see not only the ghosts of women of color in the machines of modernist innovation but also how the tensions of fame, anonymity, envy, and projection (congealed through the figure of the Black woman) fuel the theorizations of the artist, the architect, and the analyst.

— Anne Anlin Cheng

In Close Readings, a podcast by the London Review of Books, Jonathan Rée and James Wood discuss Simone de Beauvoir’s The Ethics of Ambiguity. I didn’t know about this particular work of Beauvoir’s, but I’m compelled to read it after listening to them summarize her perspective on the individual will to be free and what one asks themselves in order to arrive at this freedom. In this work Beauvoir talks a lot about childhood, memories, and how our values are shaped and formed and later emancipated, which is a topic I’m very curious about in my own work.

In Ted Gioia’s newsletter, he shared a list of his favorite YouTube videos out right now. One that stood out and that I hadn’t seen before in all the coverage of the Nobel Prize in literature was László Krasznahorkai’s reaction when the Nobel announced his win over the phone. If you want to dig a little bit further into Gioia’s Substack, I recommend this post: Hamlet Is the Gen Z Story We Need Right Now.

James Marriott’s piece on a YouTube education includes some fantastic recommendations: Kenneth Clark’s documentary Civilisation, John Berger’s series Way of Seeing, Richard Dawkins and Steven Pinker on evolution, the philosopher Bryan Magee’s BBC show, and more. Also, staying true to my pessimistic perspective on the future of the humanities and of our society’s literacy, here’s a great essay: The Dawn of the Post-Literate Society.

My Morning Read

I cannot put down Susan Choi’s new novel Flashlight. I’m not a big contemporary reader but I decided this year I’ll read every book on the long list for the Booker Prize. This is the first one and I’m immersed in the way she depicts the lives of this family after the Korean war, their establishment in the U.S. and relocation to Japan. It reminds me a lot about Toni Morrison, about her ideas of generational trauma and its dimensions, about Marianne Hirsch’s work around postmemory. It’s a bold, complex novel that so far, I highly recommend.

My Daughter’s Evening Read

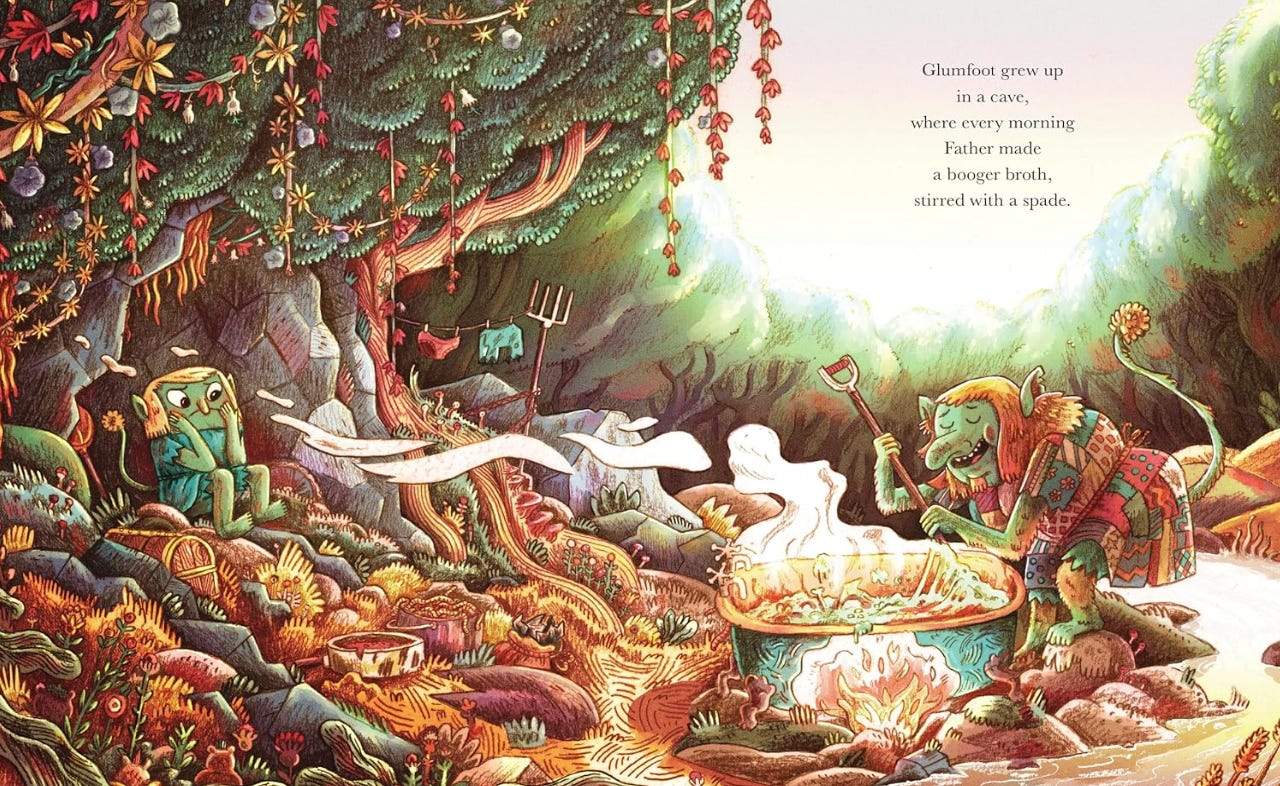

A book by the Chinese writer Yue Zhang: La Meilleure Boulangerie du Monde, that tells the story of a wolf and a rabbit who are at first scared of each other but end up making the best bread together. We’re also reading a lot of Richard Scarry. Her favorite read in english is The Cave Downwind of the Cafe by Mikey Please which was published on September 5.

What My Husband is Listening To

Boccaccio Life by Age of Chance

A Movie I’m Thinking About

La Graine et le Mulet by Abdellatif Kechiche

A POEM

Self Reliance by Ralph Waldo Emerson

HENCEFORTH, please God, forever I forego

The yoke of men’s opinions. I will be

Light-hearted as a bird, and live with God.

I find him in the bottom of my heart,

I hear continually his voice therein.

horizontal dotted line

The little needle always knows the North,

The little bird remembereth his note,

And this wise Seer within me never errs.

I never taught it what it teaches me;

I only follow, when I act aright.

Thank you Renata for all of this! I will have a look at some of your recommendations.

Regarding chronicles, in Sweden, we have the word "krönika" which is a 500-word personal piece expressing an idea, feeling and/or opinion. Once upon a time, I loved writing those for my local newspaper.

Now, it's all Substack, and I just made the decision to write solely in English, as running two stacks isn't feasible right now. All the best from Stockholm!

I love Clarice and her crônicas, and it’s a perfect way to think about newsletters. Lots of great recommendations here too!