Lauren Groff's Short Story, Dante Alighieri, and the Amazon

Some articles I read this week including Jon Lee Anderson on Brazilian politics in the New Yorker.

In this week’s newsletter: the final installment of my short story The Amazon, an article by Jon Lee Anderson in the New Yorker, my favorite Dante Alighieri canto, Lauren Groff’s short story in the Atlantic, and a new exhibition by Lucas Arruda at the Musee D’Orsay in Paris.

You can read the first two parts of my short story here: The Amazon I and The Amazon II.

The Amazon III: A Short Story

by Renata Mosci Sanfourche

The table was festive with flowers, champagne, fine silver, and chatter. Nina wiped the corner of her lips, and as she did so smiled at my mother and thought, ‘I reckon you needed someone to make you happy.’

She let her mind take her to that place she often visited when she came across a new person she couldn’t quite place.

‘Yes, it’s no secret,’ Nina thought, everyone can see she’s hiding behind her simplicity, her delicate gestures. Next to her timidity is certainly a certain elegance one hardly sees elsewhere in this room. Yet there’s something distrustful about her. Behind the smile there’s something in hiding, perhaps it’s pain and sadness, but it does come across as judgement. ‘That, oh no,’ Nina continues in her thoughts realizing she’s most definitely not a jealous woman. She went further now. She was thinking of my mother’s style, all fortune or misfortune aside, she thought it came from the interior and in that sense she was not a proper part of the picture. To all the other women, Nina included, style was an exterior force. Nina thought of my mother as a strong-willed confrontation, someone who thought it important not to conform to their standards, or at least not to show that weakness, and here she thought of the other women too. Maria also came from a modest family, but my mother seemed to be fighting for something. While Maria fell for the gossip around the table, my mother ignored all conversations around her, the main event was certainly in her mind. Nina was now bothered by my mother’s poise, realizing that at one point she too had fallen for it all as quickly as Maria did. Nina was beginning to feel all too different from her now, and she felt as though she’d lost, so she used her privilege to corrupt her guest.

‘Ana, do you want to join us next weekend at our country house? It will be just us women,’ she said to my mother.

‘She would love to,’ my father answered in her place.

Meanwhile, Nina herself was being observed by her very own husband. He listened to her as he filleted his fish. Now this was an option nearly all other guests had forgone for although they loved to eat sole not one of them learned how to fillet it except for my father, who followed his boss’s lead on the option and sitting in front of him opened his fish, a skill he learned with his mother in France. He considered Nina, agreed that she was still the most beautiful woman on the table, that she was sensitive and kind, but something about my mother’s presence had made Ana do something strange, and he felt uncomfortable by her new demeanor. And as he ate his fish he meditated on his own life, he had married Nina because he held her father to great esteem, he wished to be him one day. Now he was condemned to spend his remaining years with a woman whose novels weren’t nearly as poetic as he one day thought they would be, and although she had harbored a certain acclaim in the papers, the reviews were just as trivial as the stories she wrote and read aloud to him day and night, empty of sincerity, filled with certainties. His ideal woman was still Nina, but he wished for a woman who read the classics, who could understand beyond herself the subtleties at this dinner. Nina would quickly turn all of this into gossip and he would have to hear her plots when they were home readying for bed, time at which he wanted to sink into his pillow with Edmund Burke. Yet he feared nothing of what he did, for he was not a religious man, he followed not in the steps of great thinkers, and at least his wife didn’t judge him, and they were rich, which after all was more important than his desire to be someone else.

‘Do you prefer the sole this evening or the pirarucu this morning?’ my mother asked Nina. This wasn’t a trick question, there was no malicious intention behind it, she herself preferred the fish this evening for she had a strong aversion to fresh water fish which she often said tasted like chicken.

‘The sole don’t you think?’ Nina turned to my father, who after taking a sip of wine answered diplomatically that yes, the sole was delicious. Diplomacy had never been one to abandon him in moments like these, he knew it to be his strongest weapon, and like my mother, they saw this evening as one of the many battles they’d face before they could declare victory upon their lives. And along with the answer, my father brought to the table some knowledge about fishing. He told of the night he couldn’t sleep and walked to the port where he found two fishermen. He asked if he could go catch shrimp with them, which he did, and told of how they returned with buckets full, some of which they deep fried at the bar across the street to a shot of cachaça early that morning. The look on every man’s face, they dreamed of doing something this brave when they were kids but had never had the opportunity to do so. And then he went into another foray about eating raw shrimp, and the conversation quickly made a turn into mining trucks, and businessmen, and negotiation tactics.

‘I’ve never been to Japan,’ Nina told my mother. And as they tried to find some sort of common ground, desert had come to an end and a select few people got up to leave. And although my mother would’ve liked a small glass of sweet liquor, she thought the one glass of champagne had been enough for her and the baby and she prepared to excuse herself from the table. And as she did my father also got up, and he was also happy to retreat early from what would soon be the end of the night. He placed his jacket over her shoulders and they set off on a slow walk to their rooms.

Down she looked again into the depths of the mines. An abyss formed by the nine concentric waves of torment, red and ashy as if something had burnt through the earth and into the ground. It was warm, violent, and full of sin: the gluttonous, the violent, the insincere, the greedy, the treacherous. To their eyes, only the miners sat on the edge of these embankments, men who congregated at church with their wives, and of this she was sure. But to her eyes it was the guests at dinner that would soon inherent this wicked hole and swim in its hot fire next to Satan and his legions. And at that moment she decided she would go to church tomorrow to deliver her soul from all that which she thought was evil in her.

“Every life is in many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love, but always meeting ourselves.”

— James Joyce

News Briefing: A Man Held Hostage

I read in the news the story of a man who was held hostage by his father and stepmother for 20 years. When he was 12 years old they took him out of school and locked him up in a small room. At 32, and weighing 68 pounds, he set the house on fire; it was the only way he saw to survive.

Inside the ambulance, when fire fighters noticed a strange smell, the man told his story: he hadn’t showered in over a year, he had never seen a doctor, and his teeth were crumbling when he bit into food.

Is he a boy or a man? How could this happen in a house with a family of four: the stepmother, the father, and their two adult daughters.

A boy locked up in a room. Not a drunk. Not a criminal. Not a bum. Not an animal, not an insect, not a thing. A boy and then a man. And the girls that became women, and the father, and the stepmother, they all woke up and kept going. For 20 years they kept going. At first the school was worried about this boy who ate from the trash can at lunch. They called the house, social services, the police. Then for 19 years they all stopped calling. No one fell asleep thinking about him. They woke up too and they kept going. And the boy stayed locked in this room with nothing and no one.

Isn’t it the father’s responsibility? The stepmother? The mother? The stepsisters? The police? The school? The neighbors? What do we have anything to do with this?

And the boy, and the man, set his room on fire at 32 and 68 pounds. He set the room on fire said the news. And it’s not our responsibility. Let the man die in the room with his disintegrated teeth, with his scrappy clothes, with his books. Yesterday he sat fire to his room. The man or the boy, he set everything on fire.

A Visual Library

Currently at Rue de Chabrol

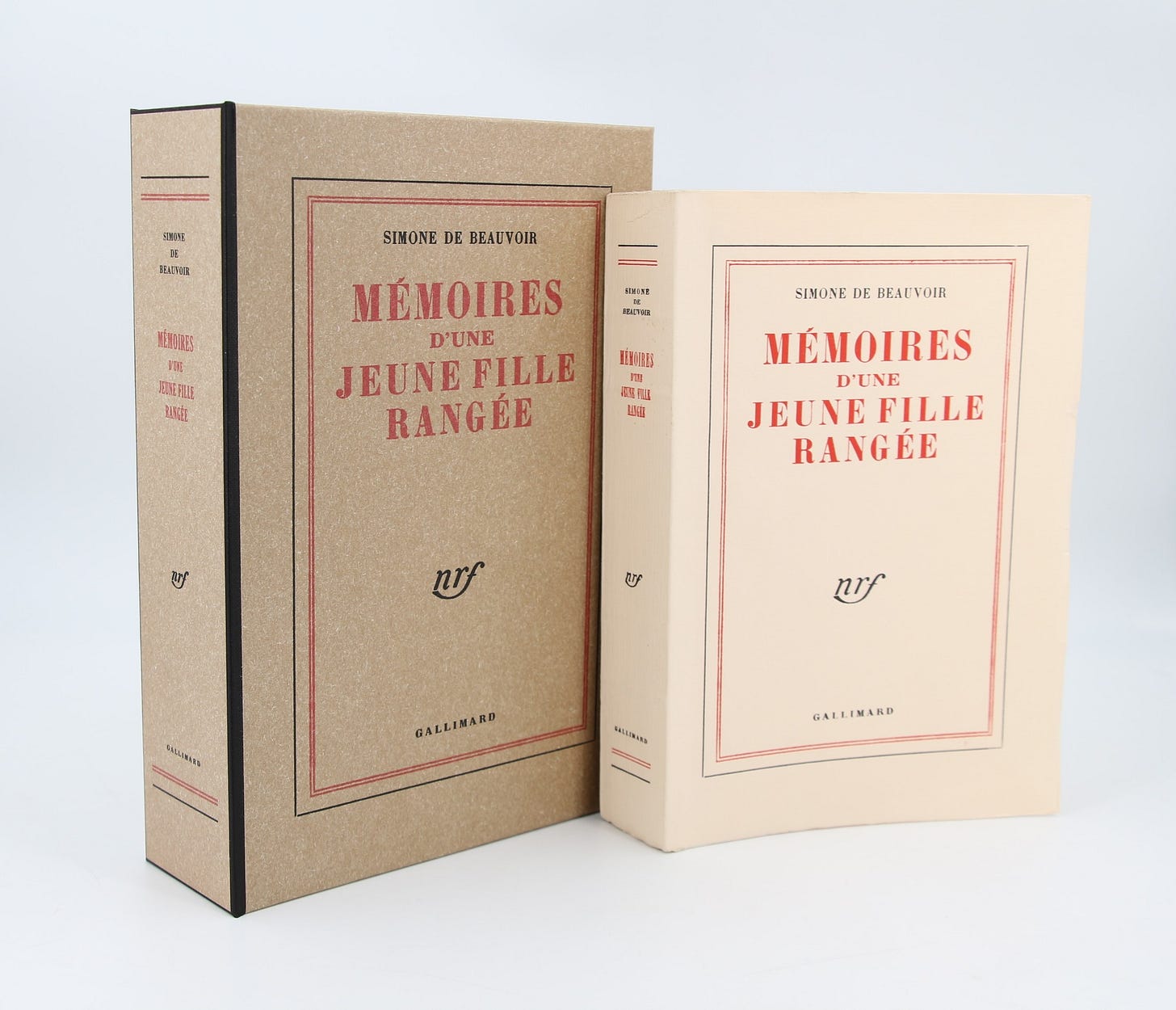

What I’m reading in the morning: in English I’m reading Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living, and in French, a friend recommended me Simone de Beauvoir as an easy read, so I’m going to try out Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter.

What my daughter is into: Vita loves chocolate and hide-and-seek so she’s naturally got only one thing on her mind and that is the easter egg hunt happening next weekend at her grandmother’s house in the South of France. We’ve also been working on her school attire because it’s getting warmer in Paris and all she wants to wear are ballet flats, which aren’t very practical when they go to the Jardin de Luxembourg with her class. She’s very into her long hair and I’m trying to convince her to get her first trim. She’s into singing out loud in the streets and screaaaaaming instead of talking.

Five things I read and saw this week:

Lucas Arruda’s exhibition “Lucas Arruda. Qu'importe le paysage” at the Musee D’Orsay, which marks the first monographic exhibition at a French museum by a Brazilian artist. On view until July 20, 2025.

This profile piece by Jon Lee Anderson in the New Yorker: “The Brazilian Judge Taking On the Digital Far Right” about Alexandre de Moraes.

I also purchased two books I want to read this weekend, one in French and one in English. In English I’m going to give “The Cost of Living” by Deborah Levy a go, and in French, a friend recommended Simone de Beauvoir as an easy read, so I’m going to try out “Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter”.

Lauren Groff’s short story “The Ghosts of Wannsee” published in the Atlantic on September 2024.

I’m still on board with Paul Krugman’s substack, where the economist is laying out for us the ins and outs of Trump’s tarrifying decisions.

What my husband is listening to:

A movie I’m thinking about:

A Woman Under the Influence by John Cassavetes

A Poem

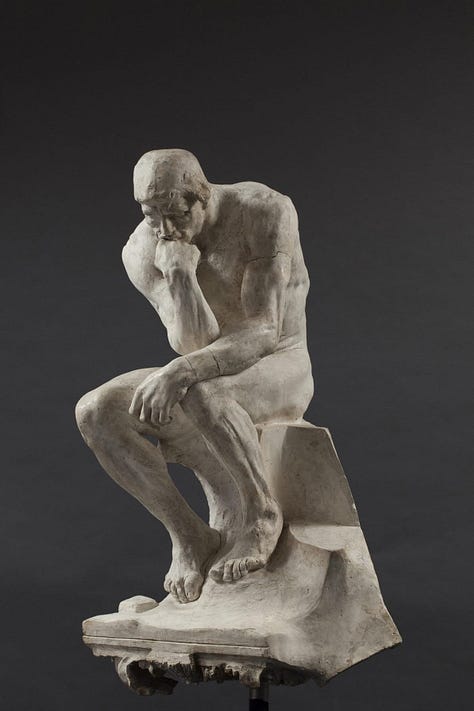

Inferno, Canto I

by Dante Alighieri

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Ah me! how hard a thing it is to say

What was this forest savage, rough, and stern,

Which in the very thought renews the fear.

So bitter is it, death is little more;

But of the good to treat, which there I found,

Speak will I of the other things I saw there.

I cannot well repeat how there I entered,

So full was I of slumber at the moment

In which I had abandoned the true way.

But after I had reached a mountain’s foot,

At that point where the valley terminated,

Which had with consternation pierced my heart,

Upward I looked, and I beheld its shoulders,

Vested already with that planet’s rays

Which leadeth others right by every road.

Then was the fear a little quieted

That in my heart’s lake had endured throughout

The night, which I had passed so piteously.

And even as he, who, with distressful breath,

Forth issued from the sea upon the shore,

Turns to the water perilous and gazes;

So did my soul, that still was fleeing onward,

Turn itself back to re-behold the pass

Which never yet a living person left.

After my weary body I had rested,

The way resumed I on the desert slope,

So that the firm foot ever was the lower.

And lo! almost where the ascent began,

A panther light and swift exceedingly,

Which with a spotted skin was covered o’er!

And never moved she from before my face,

Nay, rather did impede so much my way,

That many times I to return had turned.

The time was the beginning of the morning,

And up the sun was mounting with those stars

That with him were, what time the Love Divine

At first in motion set those beauteous things;

So were to me occasion of good hope,

The variegated skin of that wild beast,

The hour of time, and the delicious season;

But not so much, that did not give me fear

A lion’s aspect which appeared to me.

He seemed as if against me he were coming

With head uplifted, and with ravenous hunger,

So that it seemed the air was afraid of him;

And a she-wolf, that with all hungerings

Seemed to be laden in her meagreness,

And many folk has caused to live forlorn!

She brought upon me so much heaviness,

With the affright that from her aspect came,

That I the hope relinquished of the height.

And as he is who willingly acquires,

And the time comes that causes him to lose,

Who weeps in all his thoughts and is despondent,

E'en such made me that beast withouten peace,

Which, coming on against me by degrees

Thrust me back thither where the sun is silent.

While I was rushing downward to the lowland,

Before mine eyes did one present himself,

Who seemed from long-continued silence hoarse.

When I beheld him in the desert vast,

“Have pity on me,” unto him I cried,

“Whiche’er thou art, or shade or real man!”

He answered me: “Not man; man once I was,

And both my parents were of Lombardy,

And Mantuans by country both of them.

‘Sub Julio’ was I born, though it was late,

And lived at Rome under the good Augustus,

During the time of false and lying gods.

A poet was I, and I sang that just

Son of Anchises, who came forth from Troy,

After that Ilion the superb was burned.

But thou, why goest thou back to such annoyance?

Why climb’st thou not the Mount Delectable,

Which is the source and cause of every joy?”

“Now, art thou that Virgilius and that fountain

Which spreads abroad so wide a river of speech?”

I made response to him with bashful forehead.

“O, of the other poets honour and light,

Avail me the long study and great love

That have impelled me to explore thy volume!

Thou art my master, and my author thou,

Thou art alone the one from whom I took

The beautiful style that has done honour to me.

Behold the beast, for which I have turned back;

Do thou protect me from her, famous Sage,

For she doth make my veins and pulses tremble.”

“Thee it behoves to take another road,”

Responded he, when he beheld me weeping,

“If from this savage place thou wouldst escape;

Because this beast, at which thou criest out,

Suffers not any one to pass her way,

But so doth harass him, that she destroys him;

And has a nature so malign and ruthless,

That never doth she glut her greedy will,

And after food is hungrier than before.

Many the animals with whom she weds,

And more they shall be still, until the Greyhound

Comes, who shall make her perish in her pain.

He shall not feed on either earth or pelf,

But upon wisdom, and on love and virtue;

'Twixt Feltro and Feltro shall his nation be;

Of that low Italy shall he be the saviour,

On whose account the maid Camilla died,

Euryalus, Turnus, Nisus, of their wounds;

Through every city shall he hunt her down,

Until he shall have driven her back to Hell,

There from whence envy first did let her loose.

Therefore I think and judge it for thy best

Thou follow me, and I will be thy guide,

And lead thee hence through the eternal place,

Where thou shalt hear the desperate lamentations,

Shalt see the ancient spirits disconsolate,

Who cry out each one for the second death;

And thou shalt see those who contented are

Within the fire, because they hope to come,

Whene’er it may be, to the blessed people;

To whom, then, if thou wishest to ascend,

A soul shall be for that than I more worthy;

With her at my departure I will leave thee;

Because that Emperor, who reigns above,

In that I was rebellious to his law,

Wills that through me none come into his city.

He governs everywhere, and there he reigns;

There is his city and his lofty throne;

O happy he whom thereto he elects!”

And I to him: “Poet, I thee entreat,

By that same God whom thou didst never know,

So that I may escape this woe and worse,

Thou wouldst conduct me there where thou hast said,

That I may see the portal of Saint Peter,

And those thou makest so disconsolate.”

Then he moved on, and I behind him followed.