The Canon Wars: Where Are We Today?

How 20th-century's most important literary decisions affected our capacity to read, write, and publish great works of literature today.

My purpose here is to observe the 20th-century canon wars and the ongoing education reforms in America to suggest ways of understanding the decline in readers today—answers that intend to hold accountable and inspire writers, publishers, critics, and readers alike.

The Canon Wars

No one person in their lifetime would be capable, even if they tried, to read the entire Western canon. This is partly the reason why the late American literary critic Harold Bloom wrote The Western Canon in 1994, where he lists more than 800 titles in Western literature preceded by a defense of 26 canonical writers.

It’s true, our human physiological condition limits our ability to read everything written throughout history during our lifetime. We have no choice but to make concessions on what we read, and in effect, what we teach. The concessions we make when we choose to read a book are as much a decision in the type of knowledge we’ll absorb and the kind of pleasure we’ll feel, as are the choices the academy makes in determining the works students will learn, the knowledge they’ll absorb, and the impact they’ll have on the future of literature, inside and outside academia.

In the '70s, with the arrival of French theorists Derrida, Lacan, and Foucault into American thought, New Criticism, the formalist movement in literary theory that dominated our teachings at the time, was urged to revise its aesthetic approach to reading. There came to be an imminent demand to restructure the syllabi of literary studies, to expand it to embrace a pluralist American perspective.

The American literary critic John Guillory, influenced by Pierre Bourdieu’s theory cultural capital, studied the initial impulse that called upon the canon’s revision. In Cultural Capital (as he consequently titled his work), Guillory ascribed the need for change to a growing need for representation of social minorities in American culture:

In retrospect it was only in the wake of liberalism’s apparent defeat in American political culture that such agendas as “representation in the canon” could come to occupy so central a place within the liberal academy. The new curricular critique made it possible for the university to become a new venue of representation, one in which new social identities might be represented more adequately, if also differently, than in existing political institutions of American society.

This phenomenon was the onset for a centuries-long debate around the academy, which would come to be known as the canon wars. On the one side stood the aesthetes wanting to center the curriculum on literature’s classic works, and on the other side the multiculturalists, wanting to rebuild the curriculum to comprise a more socially inclusive criteria.

It was a decisive period for the future of American education. And with the 1987 commercial successes of E.D. Hirsch’s book Cultural Literacy and Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, it was clear that an end to the war was near. By the '90s, multiculturalists had won and universities were reforming the canon to include noncanonical works.

For years to come, progressive and traditionalist critics would continue to do profound work around the controversy.

In her 1989 speech Unspeakable Things Unspoken, Toni Morrison questioned the constructs of quality as the central criterion for greatness in the canon, and affirmed the presence of Afro-American literature as essential to raising the standards of both culture and literary studies in America:

What is possible is to try to recognize, identify, and applaud the fight to and triumph of quality when it is revealed to us and to let go the notion that only the dominant culture or gender can make those judgments, identify that quality, or produce it.

Harold Bloom lamented the future of the humanities, “literature is not an instrument of social change or an instrument of social reform,” he said, “it is more a mode of human sensations and impressions, which do not reduce very well to societal rules or forms.” In An Elegy for the Canon, his introduction to The Western Canon, Bloom would refer to the reformers as the school of resentment1, and was determined to maintain an aesthetic approach to teaching and reading the Classics:

A poem cannot be read as a poem, because it is primarily a social document or, rarely yet possibly, an attempt to overcome philosophy. Against this approach I urge a stubborn resistance whose single aim is to preserve poetry as fully and purely as possible.

As the journalist Rachel Donadio pointed out in Revisiting the Canon Wars, the outcome had presented us with a sort of ironic reversal in literary studies:

[John] Searle also noted a “certain irony” that the Western canon, from Socrates to Marx, which had once been seen as “liberating,” was now seen as “oppressive.” “Precisely by inculcating a critical attitude,” Searle wrote, “the ‘canon’ served to demythologize the conventional pieties of the American bourgeoisie and provided the student with a perspective from which to critically analyze American culture and institutions. ... The texts once served an unmasking function; now we are told that it is the texts which must be unmasked.”

It was true, the very works that taught us to think, were the works we were now being asked to reconsider. And with the academy restructuring the concerns of literary studies, making less space for aesthetic conversations in classrooms, it became nearly impossible for critics to contest the “balkanization of literary studies,” as Bloom would put it, without backlash.

The Education Wars

This canon fodder may kill the canon. And I, at least, do not intend to live without Aeschylus or William Shakespeare, or James or Twain or Hawthorne, or Melville, etc., etc., etc. There must be some way to enhance canon readings without enshrining them.

— Toni Morrison, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken”

Today, we’re seeing the canon wars turn on its fold.

In April, President Trump’s administration canceled 85 percent of grants to the National Endowment for the Humanities (N.E.H.), placing staff on leave in preparation to redirect its resources “toward supporting Mr. Trump’s priorities.”

In August, the administration announced funding for 97 new projects, many including “work on papers relating to the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution and the Founding era,” reported the New York Times:

Shortly after the grant cancellations in April, the agency also announced that, in keeping with executive orders by Mr. Trump, it would not support projects promoting “extreme ideologies based upon race or gender.”

These series of executive orders were later used by state schools to justify book bans across the nation, including the removal of nearly 600 books—Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird and Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner for example—from a school run by the Department of Defense.

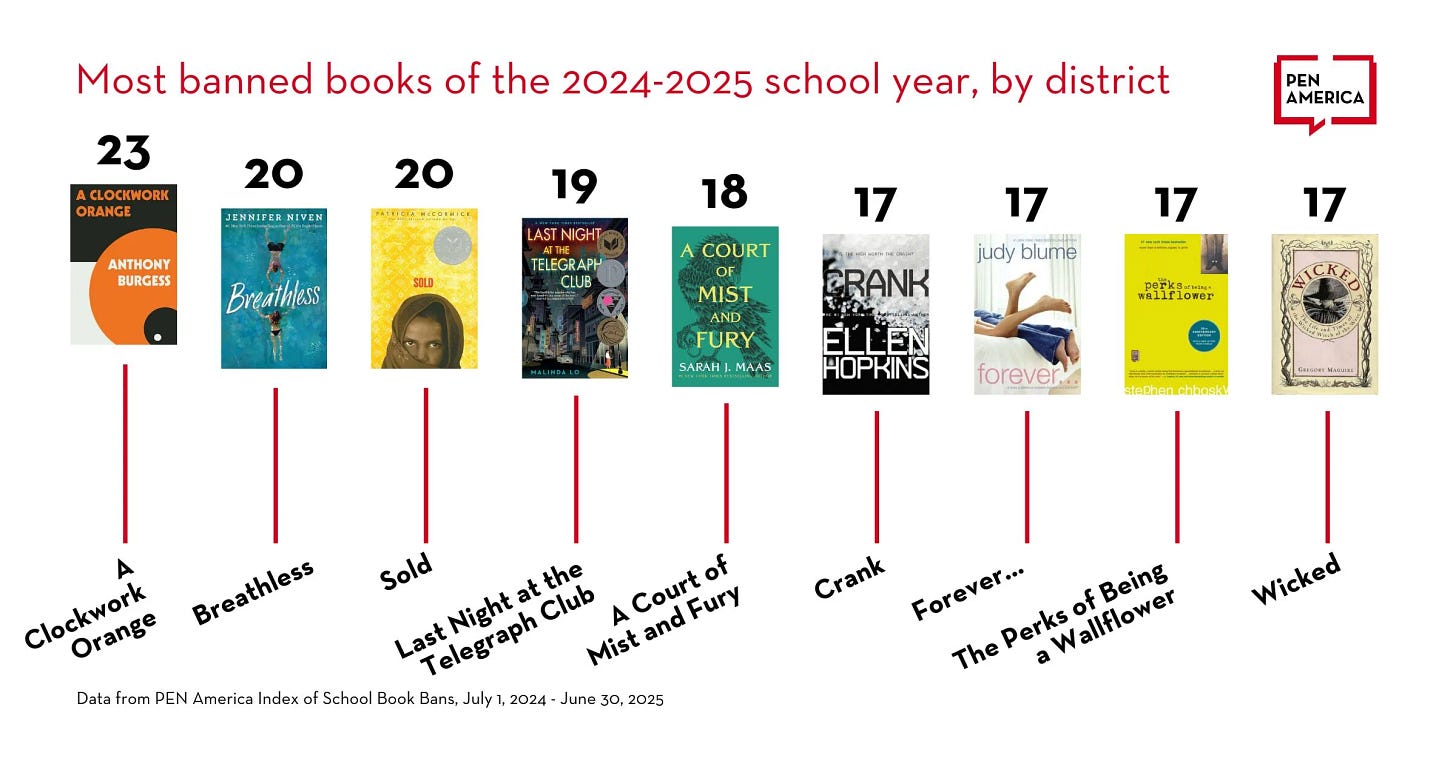

According to a report by the PEN America organization, which has been tracking book bans in America for the last 14 years, during the 2024-2025 academic school years, 6,870 books bans were recorded across 23 states and 87 school districts. A great majority of these bans were initiated by conservative parents.

Today, any progressive book or work that doesn’t conform to a particular ideology is subject to censorship. A study conducted by researchers at Cornell University found “liberals and conservatives both oppose censorship of children’s literature – unless the writing offends their own ideology.”

So far, 11 schools have banned Toni Morrison’s Beloved and five Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun. There are 11 instances where I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou was banned, and three where Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God was removed from school libraries. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, which was at one point mandatory reading at my middle school, was banned in four schools.

The federal government has demonstrated a willingness to exert excessive influence over our institutions and universities in order to serve their power agenda with a partisan national narrative. They’ve found support not only in American citizens with conservative ideologies, but in weakened university systems, which, at the first strike of a federal blow, withdrew into their academies with big plans for policy change and payoffs tucked between their legs.

The academic freedom American education was founded upon is at stake on the false premise of indoctrination: “President Trump and his allies have focused their attacks on elite universities, which they say are bastions of antisemitism and ideological indoctrination,” wrote the reporter Alan Blinder in How Universities Are Responding to Trump.

If we add the decline of our intellectual capacity to the government’s attempt to penetrate our universities, we find an entire education system on the brink of major change, one that will once again reshape our canon.

Our ability to think, speak, articulate, to understand people, to understand the differences between people, between our various natures, they depend on our capacity to read and to retain what we read.

Children and teenagers are exponentially less interested in reading. Peco and Ruth Gaskovski recently observed technology’s impact on a child’s capacity to acquire early language skills, and reported that only 41 percent of parents read books to children aged five and under, a crucial period for the development of their memory and vocabulary:

Knowing more words helps students process information more quickly, because prior knowledge of vocabulary lightens the load on working memory. The breadth and depth of a student’s vocabulary moves in tandem with their capabilities for abstract thinking. Each new word opens up a new pathway and leads to better expression of their own thoughts, as well as understanding others.

A survey by the National Literacy Trust in 2025, reported that only 18.7 percent of children and teenagers read in their free time, as opposed to 38.1 percent in 2005. If we account for the population increase in America in the last 20 years, which is approximately 44.6 million, this still means we’ve lost 48.92 million readers, that’s almost half the amount of leisure readers we estimated in 2005.

We’re not only limiting our children’s exposure to literature at home, but we’re also choosing not to stimulate their interest in books at schools. Most elementary schools in New York City have adopted a new literacy curriculum that excludes reading books cover-to-cover from the syllabi. The coursework relies on a text compilation called myBook, built on the premise of reading excerpts in order to answer questions. Since it’s the only curriculum (out of the three offered by the state) that integrates Spanish, two-thirds of schools have opted to teach it.

How are our youth supposed to use reading as recreational and educational tools, if we’re not giving them opportunities to read? In The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books, Rose Horowitch reports that only 17 percent of educators for 3rd-to-8th-grade students teach whole texts.

The Common Core, a multistate education initiative that provides the curriculum for schools in 41 American states, recently added more nonfiction readings to their syllabus because universities are prioritizing informational texts over literary ones. By 12th grade, 70 percent of assigned readings are nonfiction.

Reading is no longer taught as a tool for thought and expansion of the mind. It’s offered as prompts for answering the questions we’re asked. In other words, we’re not teaching our children cognitive skills, we’re teaching them to follow the rules, answer the questions, and not create new ones.

By the time students are ready to start their higher education career, it’s far too late to convert them into passionate readers. How can we teach them the rewards of solitary reading? If we’re not invested in creating passionate readers, does it come as any surprise that literature departments across the country are seeing a drop in enrollment?

In The End of the English Major, a 2023 article in the New Yorker, Nathan Heller reported that between 2012 and 2020, humanities enrollment declined by 17 percent in American universities:

The trend mirrors a global one; four-fifths of countries in the Organization for Economic Coöperation reported falling humanities enrollments in the past decade. But that brings little comfort to American scholars, who have begun to wonder what it might mean to graduate a college generation with less education in the human past than any that has come before.

It seems like the cultivation of the mind is no longer as much of a priority as the quest toward lucrative positions in our economic world:

At Columbia University—one of a diminishing number of schools with a humanities-heavy core requirement—English majors fell from ten per cent to five per cent of graduates between 2002 and 2020, while the ranks of computer-science majors strengthened.

Students enrolled in Columbia’s humanities program are “bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester,” Horowitch reported. Having never been asked to read an entire book in secondary schools what else could we expect: “It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading. It’s that they don’t know how.”

Unfortunately, nothing will ever be the same because the art and passion of reading well and deeply, which was the foundation of our enterprise, depended upon people who were fanatical readers when they were still small children. Even devoted and solitary readers are now necessarily beleaguered, because they cannot be certain that fresh generations will rise up to prefer Shakespeare and Dante to all other writers. The shadows lengthen in our evening land, and we approach the second millennium expecting further shadowing.

— Harold Bloom, “An Elegy for the Canon”

Literary Renaissance or Literary Doom2

Is this reversible? Will there be a moment in time when we will see a renaissance in literature? Will our society find the passion to read deeply again? Will we acquire the knowledge needed to understand and retain literature?

These are the questions some of my contemporaries are trying to answer.

In The Dawn of the Post-Literate Society, Times columnist James Marriott suggests we’re living through a counter-revolution to the reading revolution that turned the 18th-century population into prolific readers. Marriott takes us through what he terms a post-literate society, all the way to the end of democracy. Like many other critics, he attributes our dying interest in literature and reading to excessive screen-time, which he in turn equates to people’s growing incapacity to think critically.

I’m also disappointed by the present state of intellectual thought in literature. We’re no longer living through the exciting times of the canon wars, arguing between aesthetics and diversity. Yet, it’s shortsighted to attribute the state of our literary landscape to the reduced attention-span caused by technology, and it also doesn’t move the conversation forward.

If we had succeeded at inspiring our children to become passionate, deep readers, and encouraged teenagers to seek out cognitive power over social and economic power, perhaps today we’d have a larger cohort in favor of reading over scrolling. The data only highlights how American society continuously fails their children in literary instruction.

We’ve failed the literary discipline as parents, as instructors, and as institutions, but also as writers, publishers, and critics. It’s hard to admit, it’s easier to transfer this responsibility to Silicon Valley CTOs and Wall Street fat cats. I’m not saying they’re exempt from responsibility, but until we can admit our own fault, and attempt to educate and inspire people with audacious work, change cannot be imminent.

Our Collective Failure

Perhaps the canon wars were such a prominent literary phenomenon in the '90s because they foresaw today’s crisis.

It’s impossible to estimate whose approach was correct, but it’s also impossible to ignore that restructuring the literary canon to reflect identity politics did little to engage our society to read anew.

On one side, aesthetes aimed at a wider audience by focusing on form, beauty, on the sophisticated experience of reading. We can’t say today that their elitist approach would’ve avoided the mass indifference we see toward reading, but we also can’t say the progressive approach was effective.

Above sophistication and inclusion, above the elitist and the democratic, general education today ignores an important part of reading, which is the pleasure, the transformative possibilities it holds when a reader is connected to the otherness of a writer.

Morrison and Bloom were both right to believe the canon wars put at risk the future of literature. In the midst of this battle, the American writer lost purpose and instruction, we failed as a collective to inspire our society to widen their outlook. We felt compelled to engage in political discourse, to be partisan, and reading became a way to reinforce and propagate individual rhetoric. Once upon a time the author was the mind of the American nation, when the author could observe society from afar, experience social constructs from the bleachers, measure the present against the past. That was when they told powerful stories.

It’s not the writer’s job to belong, yet here we are succumbing to the pressures of contemporary demands, writing what’s in, publishing what’s agreeable. Today, we are no more than another piece working in the nucleus of the world. After all, we have been instructed to fit in, to answer the questions, not to create new ones remember? It is a misfortune, the federal government isn’t taking us toward the expansion of thought, they’re taking us to the place where they can define it.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “The mind, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.” Haven’t those of us who’ve read Shakespeare, Dante, Woolf, and Proust (to name a few) experienced those moments when what we’re reading surpasses our capacity, our own nature?

Not everyone passionate about reading is reading to find a masterpiece, not all our readers are looking for innovation, for the sublime. But there is a chance, that if a reader falls upon a book that has these qualities, their approach to literature may forever be changed.

Those established in literary culture, the critics, look at literature as a medium, look for excellence, it’s their job to praise great texts so passionate readers can encounter the other, connect with the other, perhaps even feel enriched by the other. The motivations for reading are countless, and all experiences are valid. Yet, without the dance between writer and reader there’s no longer a literary body, when one fails the system fails, when all fail the system no longer exists.

It’s been 140 years since the French poet Stéphane Mallarmé criticized 19th-century writers in the verses of Le Vierge, le Vivace et le Bel Aujourd’hui:

Un cygne3 d’autrefois se souvient que c’est lui

Magnifique mais qui sans espoir se délivre

Pour n’avoir pas chanté la région où vivre

Quand du stérile hiver a resplendi l’ennui.

“A swan from another time,” Mallarmé laments the loss of beauty, the loss of the writer and the word’s capacity to go beyond its environment. He was urging writers to go deeper, to transcend traditional narrative forms to achieve a higher aesthetic and symbolic experience in their works. His approach heavily influenced James Joyce, who went on to produce works of great value about the complexity of the human experience and identity.

Like Mallarmé’s contemporaries, we have also become overly literal, concerned primarily with the representation of reality. We’ve lost touch with our nature because of our preoccupation with individual politics. Our literature today is permeated with social commentary, they mirror everyday life, rarely do they inspire a mystical experience.

As a group of literary thinkers and writers, we have succumbed to the power fame feeds us, to the validation success brings, to social commodities, transactional feats, to the pressures of politics. We’ve let these forces envelop us, validate our anxiety to influence and have an impact. The quality of contemporary literary fiction reflects this very climate. We’re anxious about our status:

When simplicity of character and the sovereignty of ideas is broken up by the prevalence of secondary desires, the desire of riches, of pleasure, of power, and of praise,—and duplicity and falsehood take place of simplicity and truth, the power over nature as interpreter of the will, is in a degree lost; new imagery ceases to be created, and old words are perverted to stand for things that are not; a paper currency is employed, when there is no bullion in the vaults.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson on Nature

As literary fiction writers we must take risks with confidence and confront the very system we’re conforming to. David Brooks offered a refreshing observation of the artist’s role in his recent New York Times op-ed When Novels Mattered.

Given the standards of their time, Edith Wharton, Mark Twain and James Baldwin had incredible guts, and their work is great because of their nonconformity and courage.

Most important, if you don’t have raw social courage, you’re not going to get out of your little bubble and do the reporting necessary to understand what’s going on in the lives of people unlike yourself — in that vast boiling cauldron that is America.

I’d like to offer some exceptions to my critique, but it’s impossible, only time can reveal them to us. I can however present a case study around the early literature of Sally Rooney.

In Conversations with Friends, she observes the possibilities for intimacy vis-à-vis social constructs, how the transactional nature of our society, among other factors, may weigh on people’s capacity to be passionate. Yet Rooney’s novels are hardly criticized through this framework. Alexandra Schwartz, a staff writer and literary critic at the New Yorker, reviewed Rooney’s novel primarily as a love story and affair, which it is, but the urgent messages that needed to be extracted from this novel and communicated to the reader, were much greater than this simple narrative.

In the few instances we publish literary fiction with strong theory, our critics aren’t able to grasp the philosophy deepening the work. They are stuck in the multiculturalist reading, unable to read for the form, for the aesthetic values.

How can criticism serve our passionate readers, pressure our greedy publishers, or inspire our writers, when it’s become candy with no taste? “It is not ‘literature’ that needs to be redefined; if you can’t recognize it when you read it, then no one can ever help you to know it or love it better,” Harold Bloom said.

The canon wars gave rise to a new library, a moral one that teaches us great values—empathy, inclusion, compassion—but too few of those books teach us how to think about creation.

Readers have stopped reading writers who go beyond our limitations, not because they want to, but because there aren’t many new ones being offered to them, and the ones that do exist, are presented to the public as metaphors without meaning. Emerson wisely concluded, “Each age, it is found, must write its own books; or rather, each generation for the next succeeding. The books of an older period will not fit this.”

American publishers in their concern for financial success, have failed to connect reader and writer. They’ve resorted to entertainment, they’ve let pass a marginalia of text that do no more than underestimate the reader’s capacity.

The defiance in our practice must rise alongside our determination to form deep and passionate readers. We need to confront the publishers who don’t consider writers without a social following. We need to rescue our youth from dwindling institutions. We need to review the concessions we’ve made because we thought conforming was a priority.

Literary Renaissance

Where is the genius sleeping?

Our literature departments have grown so small, identity politics have eaten such a large slice of its pie, perhaps the study of the Classics is not as far away as we once imagined.

In Ignore the Pessimists — we are living through a literary golden age, Henry Oliver observes the rise of nonliterary readers revisiting the Classics, and encourages us to adopt a more optimistic outlook toward the future of literary fiction.

Adam Walker observes that historically, most renaissances happened outside of academic institutions, he also believes a literary revival has been set into motion.

Even Harold Bloom wasn’t so pessimistic about the future:

I do not believe that literary studies as such have a future, but this does not mean that literary criticism will die. As a branch of literature, criticism will survive, but probably not in our teaching institutions.

The future of literature is certainly not in the hands of our academic institutions. We’re already seeing this shift. Among the writers teaching literature outside the traditional academic environment is Garth Greenwell, who takes on Western giants like Augustine’s Confessions in a private Substack course. Henry Eliot studies Tolstoy and Kafka with his readers. And there’s the Catherine Project, a five-year-old digital initiative offering seminars on Homer, Plato, and Aristotle.

Many of us have continued to read despite the widespread use of technology, and we will continue to do so. “The common reader is still out there,” Oliver says, and I believe him. Now it is up to them to decide how they’ll engage with literature, if it’s in the context of aesthetics or social justice, and it’s up to our literary critics to properly orient us all.

I don’t believe all writers are created equal, nor all readers. To those instructed in Shakespeare, contemporary fiction entertains, to those instructed in contemporary fiction, fantasy entertains. What happens next?

The future is in the hands of the writer, and writers capable of genius can emerge, they will emerge, but they must come with nerve, it’s a vicious undertaking to confront convention today.

The School of Resentment is a term Harold Bloom coined to describe literary critics and theorists who promote a canon that includes works about social justice and identity politics at the expense of aesthetic considerations.

The term “doom” comes from Kill Your Inner Doomer, an essay by the philosopher Jared Henderson.

Cygne (Swan) in French is pronounced the same way as Signe (Sign).

Where are we today?

Two writers whose work, for me, absolutely fits the criteria of intellectual bravery are Samuel R Delany and Dennis Cooper. When I read Frisk I was utterly shocked. I had never experienced a book that confronted the reader in such a way. I cannot imagine anything like that getting published now, and if it was, it would almost certainly be misinterpreted to death.